Nancy vs. Oakland (Part 2)

Joan Brann, Nancy Reagan, + "Just Say No"

The following is an excerpt from p. 77-84 of Chapter 3, “Nancy vs. Oakland: What Advocates Can Learn from the Origins of ‘Just Say No’” from my first book, we’re here, we’re high (2018):

[Note: this chapter owes its life to Emily Dufton’s 2017 book, Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America. The writing which I present here draws heavily on Dufton’s research. Much of the information below was obtained from Chapter 10 of her book, entitled “The Truth Behind Just Say No.” Interested readers are heartily encouraged to read Grass Roots.]

[This is the 2nd in a 3-part series. See Part 1 here.]

Some context is necessary to understand the implications of Nancy Reagan’s involvement in Joan Brann’s project. Nancy Reagan was the least popular first lady in history when her husband took office in 1981. At the time, she was desperate for a hot topic with which she could win public admiration. Drug use among children, of all things, was the topic she chose to propel her into the spotlight. Part of this reasoning had to do with demographics. Staying true to a long tradition of voter-approval-via-public-sentiment, the Reagans latched onto issues of concern to one of their primary voter bases: parents.

The 1970s had seen a liberalization of cannabis laws in 10 states and Washington, DC. Throughout the decade, rates of drug use had risen. By the early 1980s, massive numbers of parents had caught on. They lectured their children and spoke with other parents in an effort to fight the apparent flood of flora and chemicals streaming through their neighborhoods.

In her book Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America, Emily Dufton paints an intriguing portrait of the parent movement that arose in the 1980s. Dufton explains that this surge in antidrug sentiment occurred at precisely the same time that Nancy Reagan was in need of an issue with which she could win public affection.

The decision to embrace the issue was ultimately not even made by Nancy, but by her advisors. Drug use among youth would be Nancy’s hot-button issue. This worked perfectly with Ronald’s attitude toward criminal justice and drug policy.

These were the circumstances under which Nancy was introduced to Oakland Parents in Action. Tom Adams and Joan Brann saw in the situation an opportunity for exposure, support, and growth. What did Nancy Reagan hope to get from the situation? The visit was a move on her part to garner grassroots support and simultaneously create a corporate opportunity for her friends at Proctor & Gamble.

Nancy Reagan’s visit to OPA took place on July 3, 1984, with much fanfare and media attention. Classroom number eighteen in Longfellow Elementary School in North Oakland provided the setting. During the visit, Reagan played a thirteen minute film that the National Institute on Drug Abuse made to warn against drugs. Afterward, Reagan made a brief statement to the group and concluded with “So let’s make it count and just say ‘no’ to drugs.” The visit itself was filmed, and another video was made about the event. Six months later, that video was played for a room of students at Peralta Year Round Elementary School. Upon viewing the video, one of the students, a twelve-year-old named Nomathemby Martini, responded by asking, “Well, why don’t we start a club against drugs and call it ‘Just Say No’?”

Brann felt it was an excellent an idea, and started to formalize the concept. In response, Brann, Adams, and another Oakland parent established the Just Say No Foundation (a new project distinct from OPA). Adams saw opportunity and once again snatched the role of president. Within a month of Nomathemby’s suggestions and Brann’s enthusiastic response, word made its way back to Nancy Reagan. Thrilled with the idea, she started handing out buttons proclaiming “Just Say No” to children at the White House.

It was also around this time that Adams’ DC connections begin to churn out tens of thousands of dollars to go toward the Just Say No Foundation. The National Association of Broadcasters started to publicize the club across the US, also thanks to Adams. By April of 1985, still less than one year after Reagan’s first visit to Oakland, Just Say No had developed into a massive national campaign. With Reagan’s support, several Just Say No marches were organized and took place in multiple cities on April 26, 1985. Within weeks there were 5,000 new Just Say No clubs formed in schools around the U.S.

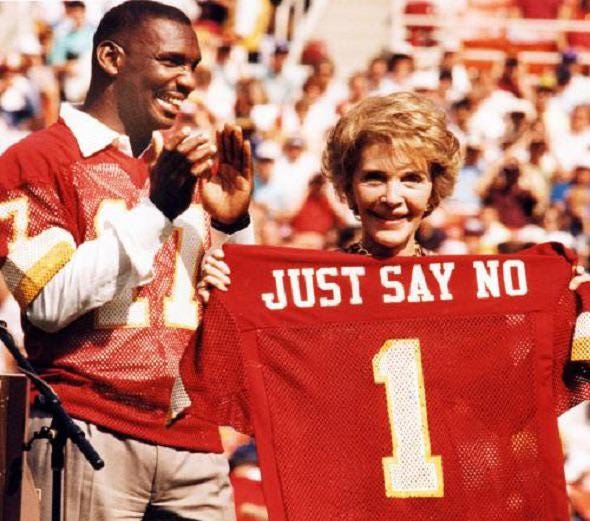

By this point, the project had clearly lost its focus on marginalized urban youth. The next time Nancy Reagan spoke in Oakland, it was not to a room full of families in a rough neighborhood, but to a stadium audience for the San Francisco 49ers. One year after the Just Say No marches, the number of clubs had more than doubled, with over 10,000 active Just Say No clubs. Around this time, the origins of the project were lost on the public. What began as an earnest attempt to help impoverished families had turned into a national ad campaign. Meanwhile the youth in Oakland remained hungry, and the flood of drugs stayed flowing.

Reagan and others co-opted the narrative around Just Say No. The origin story became streamlined, to the point of ignoring Brann’s existence entirely. In a televised speech in September, 1986, Nancy Reagan did just that, when she said,

Not long ago in Oakland, California, I was asked by a group of children what to do if they were offered drugs, and I answered ‘just say no’. Soon after that, those children in Oakland formed a Just Say No club. And now there are over 10,000 such clubs, all over the country.1

Throughout the speech, Reagan makes not a single mention of Brann, whose brainchild the original program was. In the same speech, she declared, “we can help by using every opportunity to force the issue of not using drugs to the point of making others uncomfortable.”2 This clearly differs from Brann’s original strategy of fighting drug abuse with food, shelter, and community. Brann hoped that by providing comfort for those in need, they would be less inclined to use drugs. The first lady meanwhile insists that her audience disregard the comfort of others, on national television.

The speech said nothing of Joan Brann, Tom Adams, or the actual child, Nomathemby Martini, who coined the concept. But for the national audience, this is probably the most information they were ever given about the project’s origins. Some within the Black Oakland communities which the project was intended to help began to openly doubt its efficacy and sincerity. One of the original Oakland organizers who worked alongside Brann, Avery Carter, explained, “what does upset us is the fact that many Black people do not know how the program actually started; this has not really been effectively communicated in all the literature that has been developed by some agencies.”

Hold on, it gets worse. Just five months after Reagan’s televised speech, her friends at corporate giant Proctor & Gamble enter the scene. This is when they approach Adams and ask for “exclusive use” of “Just Say No imagery” in exchange for $150,000. Nancy Reagan, who by then was the name and face that Just Say No revolved around, warned Adams, “If you don’t say yes to P&G, I’m pulling out of Just Say No.” She also insisted that he add an executive from Proctor & Gamble to the staff of the Just Say No Foundation.

Adams somehow decided it was right to take her up on both suggestions. He soon accepted Proctor & Gamble’s request. Furthermore, he created a new executive director position for the Just Say No Foundation and installed Ivy Cohen, of Proctor & Gamble. In the role of executive director, Cohen (and with her, Proctor & Gamble) gained tangible control over the direction of the Foundation. Within a year of her hiring, she appointed a senior vice president of marketing at Proctor & Gamble to serve on the board for the Foundation, as its chairman. His name was Wallace Abbot, and he soon began taking orders directly from Proctor & Gamble regarding his work with Just Say No. In spring of 1988, Abbot received direction to eliminate both Adams and Brann from their positions at the Just Say No Foundation. By August of that year, they both resigned. By the end of the year, the Foundation’s Oakland office closed, never to be re-opened. At that point, as Emily Dufton explains, “companies like Frito-Lay, MasterCard, Members Only, and McDonald’s had all used the Just Say No image in their marketing campaigns, and all had experienced a boom in profits as a result.”3

Meanwhile in Oakland, the drug use continued unabated. The city still experienced dozens of drug-related murders each year. What had been accomplished? A community of Oakland activists had essentially been conned into ceding control to federal and corporate executives. Brann was acutely aware of the mistake she had made. In 1986, A Guide to Mobilizing Ethnic Minority Communities for Drug Abuse Prevention was published. The booklet was produced by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and contained a fair amount of material about Joan Brann and OPA. In it, a warning is made. Organizers, it says, “must never lose their identity with the community and they should be particularly wary of going uptown either geographically or spiritually.”4

We still have much to learn from Brann and her situation. Most people who are familiar with the phrase “Just Say No” know nothing of its origins. It is associated with Reagan-era conservative stiffness toward drug use. But few would suspect “Just Say No” to have origins in a somewhat radical program in a Black Oakland community. In this story we see how a sincerely intentioned project can turn into a trainwreck while managing to further empower those who already have too much. It is almost as if the institutional power structures learned that the approach they had taken toward the Black Panthers (murder and imprisonment) was too blunt. Instead, they learned how to slyly co-opt a similar program, Oakland Parents in Action, and turn it into a marketing scheme, all while erasing OPA’s original legacy.