Nancy vs. Oakland (Part 1)

The origins of "Just Say No"

The following is an excerpt from p. 71-77 of Chapter 3, “Nancy vs. Oakland: What Advocates Can Learn from the Origins of ‘Just Say No’” from my first book, we’re here, we’re high (2018):

[Note: this chapter owes its life to Emily Dufton’s 2017 book, Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America. The writing which I present here draws heavily on Dufton’s research. Much of the information below was obtained from Chapter 10 of her book, entitled “The Truth Behind Just Say No.” Interested readers are heartily encouraged to read Grass Roots.]

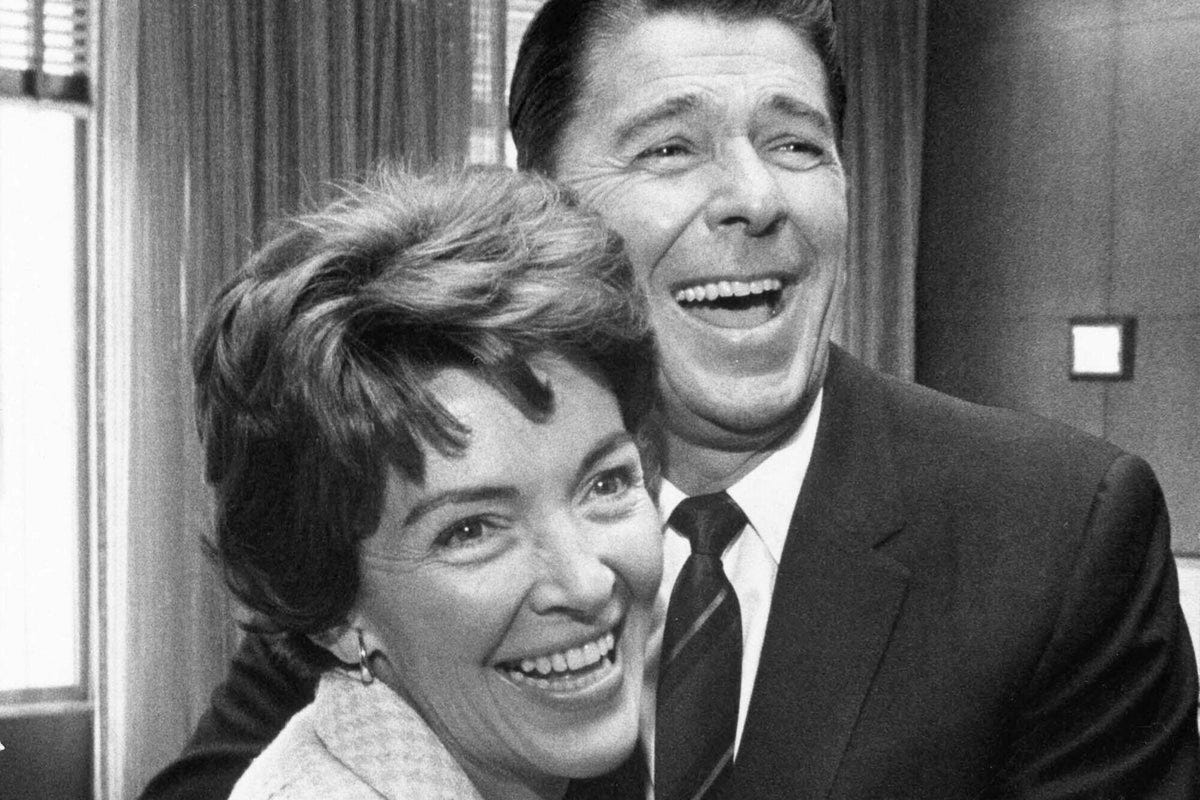

“Just Say No” is a well-known (if a bit outdated) clarion call against drug use. The phrase was popularized by Nancy Reagan in the 1980s. At the time, her husband, and then-president Ronald, was ramping up the War on Drugs. A generation later, public opinion on drug use has shifted. The same phrase which once adorned advertisements and pledge cards is now laughed at, often made the butt of drug-themed jokes. But very few know the origins of this phrase, and the program behind it in Oakland, California.

The birth of “Just Say No” is a story of special interest for any interested in drug policy, but also for any interested more broadly in the struggle against white supremacy. Echoing the Black Panthers of the previous generation, in 1984, an Oakland resident named Joan Brann started a program to feed and educate impoverished Black children while offering them a safe space to be with their families.

One of the reasons Brann started this program was to provide a haven against the flood of illegal drugs which hit Oakland in the same time period. But that was not the only reason. She wanted to see her community thrive. Unfortunately, her efforts would get caught up in a gridlock of corporate and political interests. The noble project she initiated in North Oakland would morph into “Just Say No” and reduced to a trite marketing campaign.

From this story, modern advocates can learn much. In the birth and death of “Just Say No,” we find stark examples of US power dynamics. We also see how they affect local and national conversations on drug use. Part I of this chapter explores the origins and implications of “Just Say No,” which took place in Oakland, California. Part II explores Oakland’s cannabis equity incubator program that has taken shape in recent years. The program exists to provide Oakland residents a chance to succeed in the cannabis industry. Later, we’ll see what modern cannabis entrepreneurs in Oakland can learn from their own city’s history with the Reagans’ favorite catch-phrase.

I. Joan Brann and the Birth of “Just Say No”

The story begins in 1930 with the birth of Joan Brann. Brann was born in Oakland, California. As a young Black woman during the tumultuous Civil Rights era, Brann got involved in community organizing in the late 1950s. After years of organizing experience, she was appointed director of the African American Institute in Washington, DC. This position allowed her to work as a diplomat between US and African officials. During her diplomacy work in the early ‘80s, she also served on the board of directors for the National Council of International Visitors.

After her experience in diplomacy, Brann moved back to Oakland in 1982. Upon her return, she saw her community devastated by drugs, especially crack cocaine. She felt a strong need to do something about it. Brann’s organizing experience in the ‘50s and ‘60s combined with her diplomatic experience provided a great foundation for her new project in Oakland, which would eventually, much to Brann’s chagrin, morph into the Drug War behemoth known as “Just Say No.”

Brann saw that drug use had risen sharply in the years since her own youth in Oakland. She also saw that this rise occurred not only in adults but in youth as well. The drugs included heroin and cocaine, which was soon joined by its alter ego crack cocaine. The cocaine, which came from Colombia and elsewhere, flowed into low-income neighborhoods with tacit approval from the federal government. The simultaneous prohibition and demonization of these substances set the stage for a cultural and political attack.

As a mother and activist, this concerned Brann. She was not so naive as to blame the devastation on the drugs, however. Brann understood that the rise in drug use was merely one factor in a larger web of issues. The program she started in response tackled drug use, but it did so by focusing heavily on child care, food access, and community connection. If families had safe spaces to care for each other, and enough food to eat, Brann thought they would not be so inclined to use drugs. It was with this logic that she started a new program in Oakland in the early 1980s. Brann named the program Oakland Parents in Action (OPA).

At the time of OPA’s founding, parent groups existed elsewhere. What made OPA unique was its focus on Black, low-income families, and its strategy. Other parents groups existed primarily in comfortable suburbs of cities like Atlanta and Washington DC. Such groups’ ideologies and methods were in accord with the environments in which they developed. Unlike these other parent groups, the families in Brann’s Oakland community were up against much more difficult problems. By providing accessible support to low-income families, Brann directly challenged the matrix of domination she found herself in. OPA was a parent group but it was also a strike against oppression--a direct challenge to nation-state capitalism.

There was only one issue. OPA relied on grant money from a local philanthropic organization to operate. Furthermore, their access to the grant depended on Brann’s rapport with Tom Adams, another parent activist from Lafayette, a town about ten miles northeast of Oakland. What began as a well-intentioned collaboration soon opened the door to the Reagans’ involvement, which shortly thereafter led to the downfall of the program.

Brann initially met Adams through her neighbors, with whom she shared her dreams for a neighborhood program to address drug use among youth. It was Adams who suggested that Brann apply for a grant through the San Francisco Foundation. She did, and the grant allowed OPA to launch, in March 1984. Unfortunately, despite Brann being the primary architect of the program, in a move typical of US power dynamics, Adams claimed the role of “president” of Oakland Parents in Action--despite being a well-off man of privilege from a suburban town 40 minutes outside the city. Brann, the Oakland native and project mastermind, was declared “projects director.”

Adams taking the role of president over Brann was the first in a series of moves that shifted power away from Brann and the community she served. Adams is documented saying that he was “concerned” about racial disparity in the parent movement. And indeed, he did help Brann in various ways. He tried to get her on the board of the National Federation of Parents for Drug-Free Youth (NFP), which was then the largest group devoted to the cause. Alas, NFP’s staff remained staunchly monocultural, and a board position for Brann never manifested.

We wonder, however, if either Brann or Adams knew what they were up against when they started to appeal more directly to federal programs for aid. Adams’ connections in DC would soon yield $50,000 from the Drug Abuse Fund and $22,000 from the US Department of Health and Human Services. But they also led to so much national pressure that OPA would actually cease to exist only three years after its founding. Were either Brann or Adams prepared for the implications of accepting such sums of federal money?

One aspect of this situation which is striking is how similar OPA’s efforts were to those of the Black Panthers, a decade-and-a-half earlier, in the same city. OPA provided food, child care, and education to low-income Black families, much like the Panthers had. Adams helped bring OPA to federal attention, presumably because he was proud of it. Or were there other intentions? How thrilled were the Reagans, we wonder, to learn that impoverished Black families were using federal money to feed and care for each other? Was the downfall of OPA under federal pressure a genuine mistake or a calculated move? Or perhaps somewhere in between?

The single point at which OPA’s downfall becomes, in hindsight, inevitable, is precisely the moment at which Nancy Reagan gets involved. One of Adams’ many DC connections included a woman who directed Nancy Reagan’s projects named Ann Wrobleski. Through Wrobleski, Adams suggested that Nancy Reagan come to visit OPA. Reagan had already conducted several visits to parent advocate groups as well as drug treatment centers. Until that point, however, not a single one of her visits had been to an inner-city community. Adams was keenly aware of this, and he hoped that drawing Reagan’s attention to OPA would help it thrive. Wrobleski and Reagan agreed with Adams and scheduled a visit to Oakland in 1985.

Just say Know.