"Addiction" to ultra-processed food...?

...or neo-Malthusian resource policing in the midst of global class war?

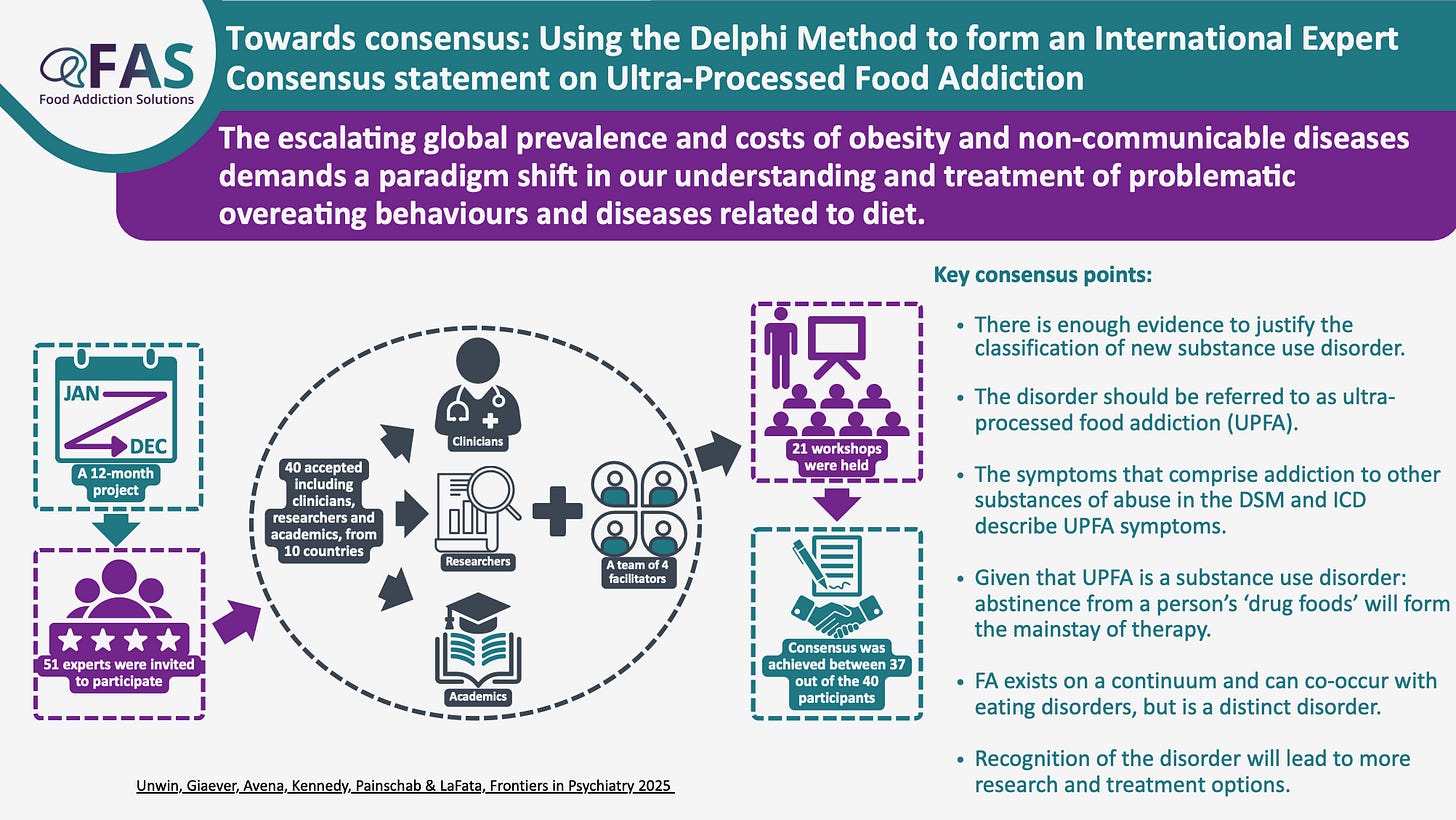

A paper was published Wednesday calling for the “formal recognition” of a new diagnosis: “ultra-processed food addiction.” Written by a coterie of scientists from institutions such as Oxford, Princeton, etc., the article is based on a study performed with the Delphi method (originally developed by RAND, the military industrial complex think-tank that serves as an auxiliary to the Pentagon) to deduce “expert consensus” on whether and why the concept of “addiction” should be systematically and pathologically applied to the consumption of “ultra-processed food.”

First, some context: in a different study, a team of Harvard scientists found that sodium consumption is responsible for 100,000 deaths each year in the United States alone. This figure is higher than the total number of deaths by drug overdose last year. On a related note, sugar activates opioid receptors, and diabetes, which is closely linked with sugar consumption, takes millions of lives annually each year around the world. Many are thus rightfully concerned about the consequences of widespread consumption of highly refined food products. But creating a new diagnosis to pathologize people for feeding themselves is not the solution.

Yes, salt and sugar can be habit-forming. No, that does not mean we lose our willpower when we consume these substances. And it especially does not mean that people’s food consumption habits should be subject to policing by a niche crowd of professionals whose field consists of increasingly sophisticated methods of gaslighting the working class (i.e., 99% of the population) for eating, medicating, and other basic life necessities.

The notion that drug use (or in this case, eating) can be, and in fact typically is, quite rational is something many are inclined to resist. This is understandable; the reality of the situation has been obscured by well over a century of mis- and disinformation regarding drug use. Such rhetoric, which paints repeated drug use as deviant behavior that warrants justification as to why it occurs, owes its proliferation to the commercial interests of the medical profession and their historical intersection with the political and economic interests of China.1

More simply: “addiction” is copaganda. It is a rhetorical device that has opportunistically developed into its own field of pseudoscience and which is used to police the behavior of the general population. That it is increasingly applied to food (and technology, and whatever else one can imagine) does not reflect its validity; on the contrary, it shows how meaningless it all is.

Many readers will already be familiar with the “abundance” discourse that has become popular recently as a rebranding of capitalist ethos for the 21st century. Abundance ideology attempts to justify and rationalize new production and distribution technologies while simultaneously navigating (but mostly just ignoring) mass economic turmoil, polycrises, and fractured (post-)globalization. Quietly lurking in the periphery of abundance capitalism, as its dramatic foil, is a stubbornly tenacious neo-Malthusianism that has thoroughly overtaken the minds of well-meaning folks who are rightfully concerned about inequity in access to food and medicine (and shelter and so on). This neo-Malthusianism demands and defends artificial scarcity by gaslighting consumers (most of whom are, let’s not forget, also workers) with rhetoric that is supposedly scientifically informed. It is on full display in the new paper calling for diagnosis of food addiction.

In response to the paper, nutrition and food science researcher Gunter Kuhnle posted an excellent thread on X (f.k.a. Twitter) documenting a conflict of interest that was not reported in the paper. Kuhnle found that the paper’s lead author, Jen Unwin, co-founder of Food Addiction Solutions, is affiliated with the Collaborative Health Community, which at one point offered a “Metabolic Health Retreat” 5-night guest package for £3,500, though Kuhnle noted that this service has since “disappeared from their website.”

It is also notable that the study uses RAND’s Delphi method to form a supposed consensus on food addiction. According to RAND’s website, the Delphi method was originally developed to “forecast the effect of technology on warfare.” One of the first documented uses of the Delphi method was a consensus-forming project for the US Army in the 1950s. Its application to food access in the general population is itself arguably a form of warfare, specifically class war, in which social murder is abstracted through fallacious concepts such as food addiction that serve as ideological weaponry for both the state and private sector.

Ironically, the very problem this new “consensus” seeks to resolve is one of the military’s own creation. Corporate food industry titans have long relied on a formula known as the “bliss point,” referring to a mathematical ratio of salt, sugar, and fat originally developed by food and computer scientists working for the military to make food rations more appetizing for troops. It was not long before the formula became common industry tradecraft and it is now utilized in countless products by a number of brands. Appetites around the world are mathematically stimulated, primed for dopamine release with military-grade technology. But when people inevitably want more affordable food, it becomes an issue.

This irony itself reflects the larger paradox of capitalism, which incentivizes consumption past its physical limits to the point of collapse and then finds new ways to profit off of the resulting devastation. Salt and sugar were among the first products ever to became global commodities largely because they are reliable sources of revenue fed by never-ending demand. And since profits are placed over people, it is only after profits take a hit that the owners of capital decide something must change.

For example, Morgan Stanley published a report on 2015 titled “The Bitter Aftertaste of Sugar.” In it, the legendary Wall Street firm explains that sugar consumption has grown so enormous that, when its economic consequences are fully measured by the guys in suits looking at spreadsheets, it has become a net negative for the global economy. Now that industry has had a full decade to reckon with this information, along comes “ultra-processed food addiction,” which could be a leading concern for public health across the globe, or maybe just a big old crock of bullshit, depending on who you ask. As Smedley Butler once said, war is a racket.

Thanks for reading.

I have already written about this in Drugism (p. 16-23) and it is explained more fully in my forthcoming High and Mighty.