William Burroughs' DMT "Overdose"

The Beat writer warned Timothy Leary not to over-hype the drug

See image credits below.

The following is an excerpt from p. 136-138 of Chapter 3, “Everywhere, All the Time: DMT and Drugism” from my new book, Drugism (2022):

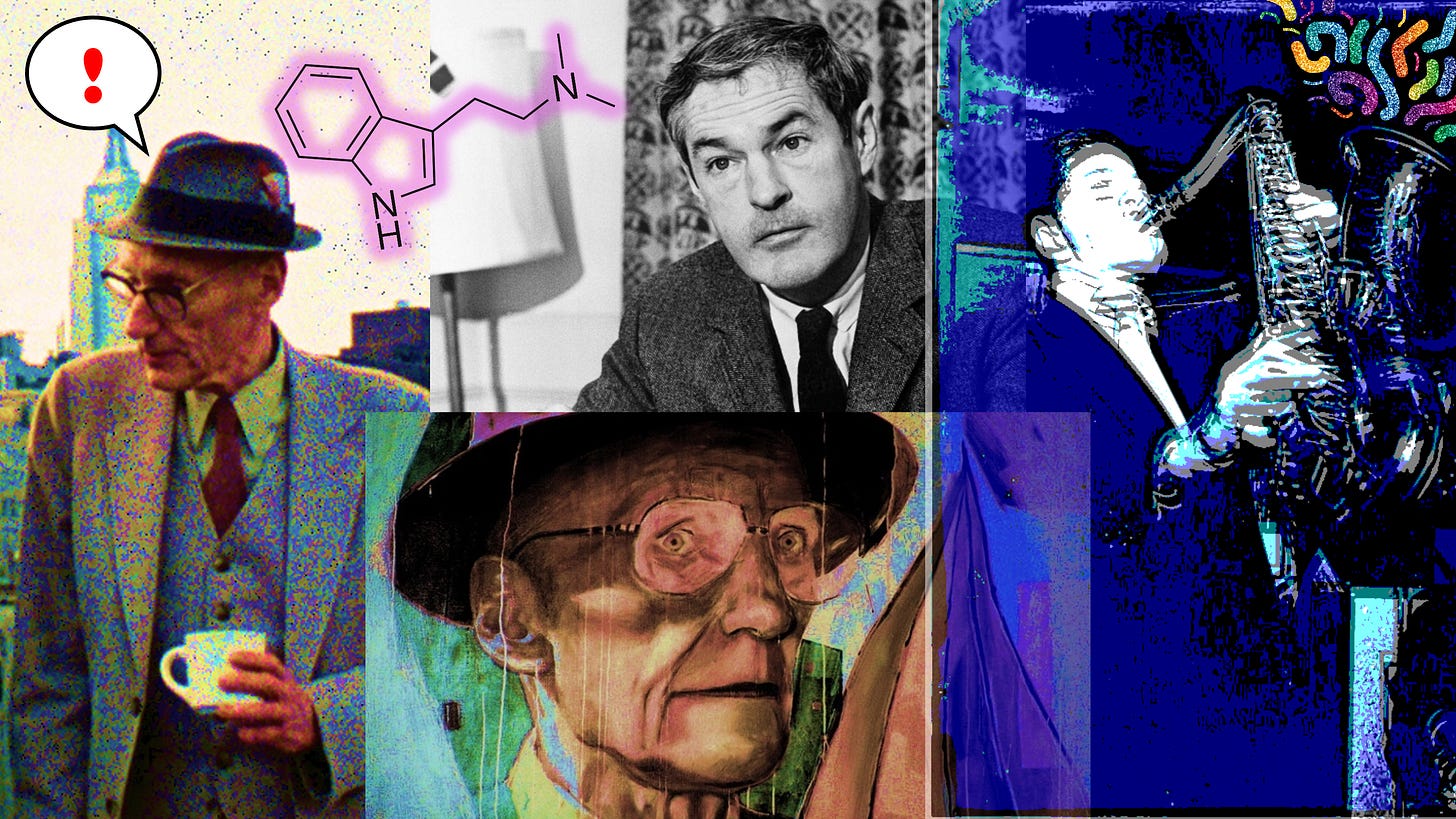

DMT started to show up in US pop culture in the early 1960s, not long after Al Hubbard had his initial DMT trips and predicted that the drug “would be worth a million dollars.” The drug spread rapidly through various circles, although it remained considerably less popular than other tryptamines like LSD and psilocybin. However, like any other drug, DMT itself held no judgment. It appeared in circles varying from jazz musicians to literary figures to the offspring of petroleum tycoons—all within a few short years in the early 1960s.

We will start with a jazz musician. You may have heard of Charlie Parker, but you probably have not heard of Allen Eager. Eager was a saxophonist who played with Parker, Coleman Hawkins, and other celebrated figures in jazz.[i] His career blossomed in the late 1940s, and in the ‘60s he was still playing and touring on the road.

Eager had a period in the 1960s when, in his own words, “I was shooting a lot of DMT.”[ii] His honesty, as well as the context of his life in which the DMT use occurred, reveal that DMT can be used habitually, even compulsively. For what it is worth, Eager also habitually used heroin. It seems that his DMT use was not unlike his heroin use: injected repeatedly, over an extended period.

Saxophonist Allen Eager had a period in the 1960s when, in his own words, “I was shooting a lot of DMT.”

Another artistically creative person who habitually used heroin made his way to DMT by the early ‘60s: an infamous writer by the name of William S. Burroughs. Burroughs’ interest in DMT traces back at least to the 1950s, when he embarked on a journey to find yagé in Colombia, described in his correspondence with Allen Ginsberg and published as The Yagé Letters. It is not entirely clear how Burroughs first learned of yagé but at least one account suggests that it may have been from a tabloid article written about the drug in the ‘50s.[iii] Both Burroughs and Ginsberg developed a fascination with yagé (among other drugs) which they pursued throughout the 1950s and ‘60s.

In addition to occupying the first wave of state-side ayahuasca enthusiasts, Burroughs and Ginsberg were also some of the first people to use pure DMT. In the same time period that Al Hubbard was using DMT in Vancouver, William Burroughs was also using it, in Tangier, Morocco.

In March 1961, while in Tangier, Burroughs received a substance thought to be DMT, which he referred to as “prestonia.” The name was borrowed from a plant that, at the time, was believed to contain DMT, Prestonia amazonica, and which had been noted by Richard Spruce in the mid-nineteenth century.[iv] Burroughs’ “prestonia” DMT was synthesized by Dennis Evans, an organic chemist at Imperial College in London [who did his postdoc at the University of Chicago, a school founded and funded by John D. Rockefeller]. Evans had also synthesized diethyltryptamine, or DET, and other compounds.[v]

Burroughs’ experiments with DMT seem to have started the following month. In a letter to a friend from April 20, 1961, Burroughs described his earliest experiences with the drug. He wrote that DMT is “exhilarating” and described “the Attack that always comes when the [DMT] hits,” followed by “rushes of numbing force.”[vi]

A week later, Burroughs again wrote to the same friend, describing another DMT trip. This one, unfortunately, he described as an “overdose.”[vii] The dose, around one hundred milligrams (coincidentally, the same amount I smoked in the experience opening the chapter), thrust Burroughs into “unendurable pain,” “unimaginable pain.”[viii] Trying to make sense of the experience, he urged his friend (and perhaps himself?) “Do not forget this...WAR. War to extermination.”[ix]

The DMT thrust Burroughs into “unendurable pain,” “unimaginable pain.”

The experience was so overwhelming for Burroughs that he took a dose of apomorphine, hoping to halt or lessen the DMT’s effects.[x]Apomorphine, as Burroughs explained in an earlier letter to the British Journal of Addiction in 1956, is a drug used for treating withdrawal symptoms. Burroughs insisted he “was never completely cured of the craving for morphine until [he] took apomorphine treatment,” and strongly urged its use in the treatment of opioid withdrawal.[xi]

How or why Burroughs got the idea to use apomorphine for his DMT overdose is not entirely clear. It proved quite prescient, however. Later research revealed that apomorphine antagonizes 5-HT2A receptors.[xii] As we learned earlier in the chapter, these are among the primary receptors affected by DMT. Of course, Burroughs was highly attuned to the pharmacological research of his era. It would not surprise me if he was somehow already aware of the relationship between apomorphine, DMT, and 5-HT2A receptors.

A few years after Burroughs’s experience with DMT and apomorphine, another opioid antagonist, nalorphine (which is structurally similar to apomorphine) was found to have psychoactive effects. This was noted by none other than Stephen Szára, the Hungarian DMT scientist mentioned earlier in the chapter. Nalorphine’s psychoactive effects, Szára elaborated, “are comparable to those of marihuana” with a “hallucinogenic dose” as low as thirty milligrams.[xiii] Decades later, Rick Strassman would conduct research into the interactions between DMT and naltrexone. However, the research was only conducted on three people, and its results were inconclusive; one participant had to stop the research because of naltrexone’s depressive effects.

Burroughs’ experiences with DMT influenced his work throughout the 1960s.

In sum, at least one drug designed to terminate the opioid high was found to also terminate the DMT high; however, a similar drug was found to produce a high itself; yet another was found to have no clear effect on DMT, but produced depression on its own. This relationship between opioids, tryptamines, and antagonists is puzzling. It presents obstacles for any attempt to define concepts like psychoactive, or to determine precisely which drugs get who high. This reinforces the importance of set and setting in determining drug effects, as well as more nuanced factors such biochemistry, diet, drug purity, etc.

Regardless, Burroughs’ experiences with DMT influenced his work throughout the 1960s. Various passages in some of his most celebrated books of that decade, like The Soft Machine and Nova Express are directly inspired by his DMT trips. Many of them can be traced back to the trip reports contained in Burroughs’ letters to friends, such as those cited above.[xiv]

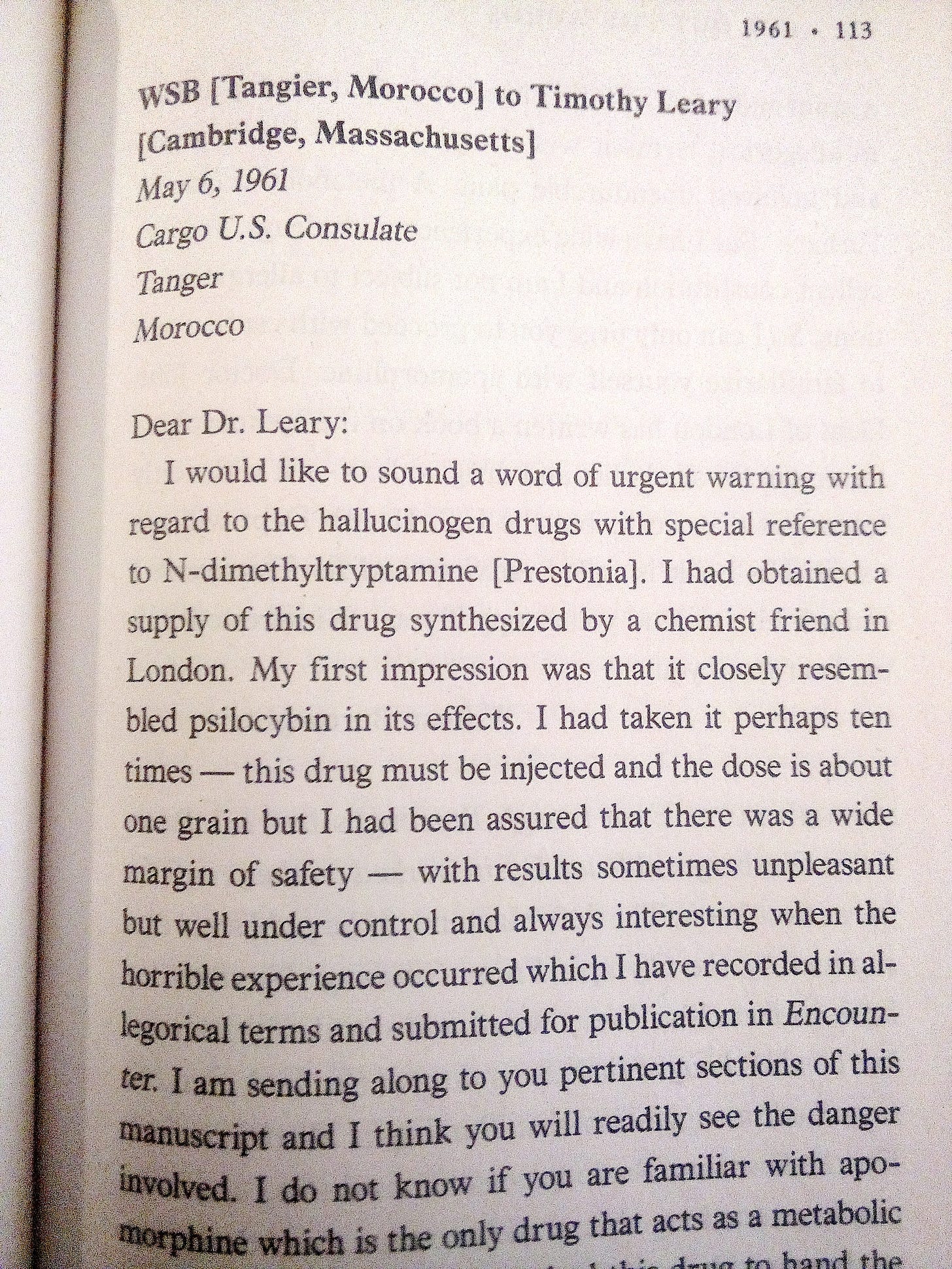

Burroughs shared his interest in DMT with others, like Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary. A couple weeks after Burroughs’ DMT overdose in Tangier, he warned Leary, who he knew was likely to praise and publicize any tryptamine he encountered. In a letter to Leary dated May 6, 1961, Burroughs explained that, while he saw value in the DMT experience, he also felt there was some “danger involved.”[xv] He expressed fear that DMT might even be lethal (although as far as we know, it is not) and urged Leary to be cautious with it. While Leary did not celebrate DMT anywhere near to the extent he did LSD or psilocybin, his social circle nonetheless became a focal point of DMT use and distribution.

[Keep reading here.]

Endnotes

[i] “Allen Eager Is…”

[ii] St John, 65.

[iii] Ibid., 21, 24.

[iv] Ibid., 397.

[v] Ibid., 29-30.

[vi] Harrop, 204, 205.

[vii] Ibid., 206.

[viii] St John, 31, 33.

[ix] Harrop, 207.

[x] Ibid., 206.

[xi] Burroughs’ letter about apomorphine was originally published in The British Journal of Addiction, Vol. 53, No. 2 and is reprinted in Burroughs, Naked Lunch. Quote taken from 220.

[xii] Newman-Tancredi, et al, “Differential actions of…”

[xiii] Szára, “The Hallucinogenic Drugs…,” 1515.

[xiv] St John, 32, Harrop, throughout.

[xv] Morgan, ed., 113.

Sources

“Allen Eager Is Dead at 76; Sax Player of the Bebop Era.” The New York Times, Jun 1, 2003.

Burroughs, William S. Naked Lunch: The Restored Text. Grove Press, New York, NY. 2001.

Harrop, Joanna. The Yagé Aesthetic of William Burroughs: The Publication and Development of his Work 1953-1965. PhD thesis, Queen Mary University of London. 2010.

Morgan, Bill, ed. “Rub Out the Words: The Letters of William S. Burroughs 1959-1974.” HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY. 2012.

Newman-Tancredi, Adrian, Dider Cussac, Yann Quentric, Manuelle Touzard, Laurence Verrièle, Nathalie Carpentier, and Mark J Millan. “Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. III. Agonist and antagonist properties at serotonin, 5-HT(1) and 5-HT(2), receptor subtypes.” The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 303(2):815-22, Nov 2002.

St John, Graham. Mystery School in Hyperspace: A Cultural History of DMT. Evolver Editions, Berkeley, CA. 2015.

Szára, Stephen. “The Hallucinogenic Drugs—Curse or Blessing?” American Journal of Psychiatry, 123(12):1513-1518.

Image credits

Photo of William Burroughs from ARTnews at https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/precarious-immortality-william-s-burroughs-on-film-5473/

Image of DMT molecule from Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N,N-Dimethyltryptamine

Photo of Timothy Leary from AP Photo via CBS at https://www.cbs42.com/news/local/timothy-leary-at-100-how-the-counterculture-icon-got-kicked-out-of-the-university-of-alabama/

Photo of Allen Eager from Wikidata at https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q2648344

Painting of Burroughs from Watkins Mind Body Spirit Magazine at https://www.watkinsmagazine.com/the-magical-universe-of-william-s-burroughs

#DMT #DET #drugism #drugs #drug #history