Precious Crystals

What do ancient salt taxes have to do with modern drug laws? Just about everything

Clockwise from top left: sea salt; an unidentified powdered drug; a salt shaker; cocaine; crack; MDMA; methamphetamine; Epsom salt. See photo credits below.

The following is an excerpt from p. 39-47 of Chapter 1, “Precious Crystals: What Salt Teaches Us About Drugs” from my new book, Drugism (2022):

The theme of salt taxation is quite prevalent through history. For students of drugs, this is particularly important, for within this historical theme lie the roots of modern drug prohibition. That’s right, ancient salt taxes laid the foundation for modern drug laws.

I. Salt and the State

China saw some of the very first salt taxes, dating back to at least the twentieth century BCE. The historian Mark Kurlansky writes that “the first state monopoly” in history was salt, in China.[i] This makes salt one of the oldest, if not the oldest, sources of tax and state revenue in global history. Seen in this light, salt is one of our oldest commodities, which holds significance for the development of later commodities, like drugs.

Ancient Chinese emperors realized salt was integral to diet and that it would therefore be a reliable source of state revenue. [Note: salt is technically not required for human life. Prior to the age of colonization, some populations did not eat salt but obtained sufficient sodium and chlorine from other sources.] Not only was salt taxed by emperors—its production and sale were monopolized by the empire and only state-sanctioned merchants could legally produce or sell salt. Anyone producing or selling salt without state approval was criminalized. This lasted more or less for millennia, with one major break starting in the first century CE and lasting roughly six hundred years. The salt tax returned with a vengeance however, in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE).[ii] Throughout China’s history, the taxes on salt have been increased in regions which lack their own salt production, allowing the state to profit from the higher demand in those areas.[iii]

The Chinese salt tax was not without its critics, however. The criticism came from various corners of society and resulted in at least two separate abolitions of the salt tax, one lasting three years, another around six hundred. The first of these occurred in the first century BCE, from 44-41 BCE. In the decades leading up to this, there had been intense debate on the political role of salt taxation, and whether it was practiced in an equitable way.

Ancient salt taxes paved the way for modern drug laws.

Forty years before the abolition, the essence of this debate had been documented with a publication called “Discourses on Salt and Iron” by Huan K’uan.[iv] Salt historian Robert Multhauf describes K’uan’s piece as a “timeless debate on the need for revenues versus injustice to the poorer classes,” and “the abuses of a state bureaucracy versus those of private ownership.”[v] Readers may notice that these are the same core issues in modern discussions of drug legalization. Although scholars like Huan K’uan and working-class salt consumers may have resonated with such arguments, China’s rulers at the time did not. Despite decades of debate, the abolition did not last long; the salt tax was reinstated merely three years later.

A century afterward, the idea that the state salt monopoly might be unjust gained more traction among the ruling class. Salt historian Kurlansky informs us of an unnamed but apparently powerful “Confucian government minister” who argued that “government sale of salt means competing with subjects for profit,” which he said was not “fit for wise rulers.” The salt monopoly was subsequently abolished “toward the end of the first century [CE].”[vi] This time, it lasted not for three years but for six hundred. The monopoly was not resurrected until the Tang dynasty, mentioned above, when salt would come to raise half of the state’s budget.

In addition to China and Kemet, salt was taxed in the ancient kingdoms of Israel, Syria, and India. Evidently the ancient Indian state, like that of China, practiced something of a salt monopoly. According to the Arthashastra, an Indian text which dates to roughly 300 BCE, salt production was overseen by government officials with a system of purchased licenses. Roughly two thousand years later, an extensive salt tax and accompanying monopoly were enforced by British colonists in their long, violent occupation of India.[vii]

The emergence of salt taxes in Europe “was concurrent with the emergence of national states, and the attendant costs of military adventure.”

The ancient Roman Empire also had its own elaborate salt tax. It is from Rome’s use of salt that we get the words salary and soldier [this point is elaborated later in the book]. And it was from Rome that many later, European populations learned to tax salt. As Multhauf explained, the emergence of salt taxes throughout Europe “was concurrent with the emergence of national states, and the attendant costs of military adventure.”[viii]

Is there something inherently connected about salt and national politics? Multhauf seemed to think so, and I would agree. The psychological force that drives people to create borders is not so different from that which drove the people around Lake Yungcheng to go war with each other more than eight thousand years ago. [Note: Lake Yungcheng, discussed earlier in the book, is the earliest known site of salt collection in China. The lake was also the site of some of China’s earliest wars.]

If we are willing to consider salt a drug, like [Pierre] Pomet was, then it would behoove us to discern what, if any, impact it has had on our consciousness. Looking at salt from such a distance, we see that one of its most reliable effects—to whatever extent there are any—is the creation of loyalty. Loyalty, obedience, respect for authority—these are the most common behavioral responses to salt consumption.[1] People tend to be extremely loyal to those who provide their salt. Once introduced to salt, people will generally do whatever necessary to get more, even if they don’t consciously realize they are doing so.[2]

The craving for salt transcends political ideologies.

The craving for salt transcends political ideologies. And it is precisely this transcendence of political ideology which makes salt so useful for nation building. You buy salt from a grocer whether or not you agree with the grocer’s politics. Therein lays salt’s power.

Just as salt taxes were foundational to China’s growth, they have proven similarly integral to the history of many other nations. It is largely because of the intense loyalty which salt generates that it was so useful in the task of nation building. Unfortunately, just as salt helped fuel nations, it also helped fuel nations’ disastrous byproduct: colonization.

After the demise of the Roman Empire and the growth of subsequent kingdoms in what is now Italy, salt taxation became a trusty way to reestablish economic order. In the development of Italy, salt was power. Colonial-era Italy continued to tax salt and tightly controlled its trade.

Along with salt, they also monopolized tobacco, which was one of the hottest new commodities at the time. A newspaper article from 1887 reporting on the Italian salt and tobacco monopolies informs us that Italian merchants who sold legal salt or tobacco were required to “display the royal arms over the door,” a sign of the merchant’s allegiance to the Italian state.[ix]

Spain was another colonial-era power that used oppressive salt tax laws to build power. There, the Crown declared ownership of the kingdom’s salt in 1348, creating a royal monopoly. Later, during the Inquisition, Ferdinand and Isabella introduced a new punishment for breaking salt laws: anyone accused was to be “shot to death with arrows.”[x] During this time, Spain obtained most of its salt from its colonies throughout the Atlantic. As a result, people who harvested or extracted their own salt rather than buying it from the colonial monopoly were killed by the Crown.

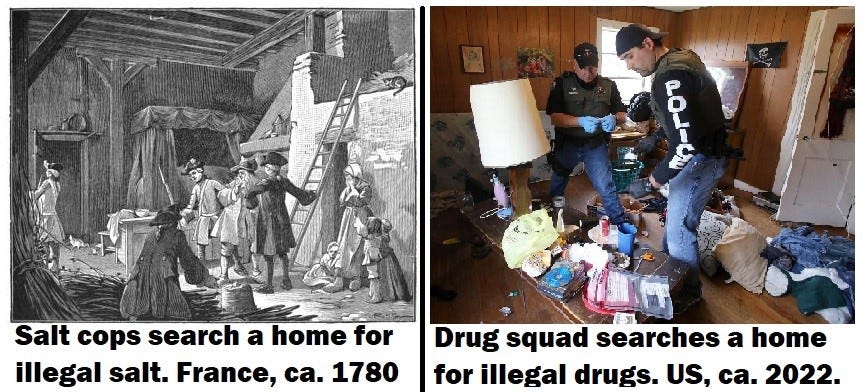

During France’s gabelle, untaxed salt was contraband; possession was punished with “a term in the galleys,” a forerunner of today’s prisons.

As rough as it must have been to be shot to death with arrows for making your own salt, there is another colonial power which boasted a salt monopoly even more oppressive than Spain or Italy: France. The French salt tax, known as the gabelle, was arguably the most oppressive salt law in history. We should note that the structure of the French gabelle greatly resembles that of the US’s own modern drug laws.

Under France’s gabelle, untaxed salt was contraband. From 1680 on, possession of contraband salt was punished with “a term in the galleys.”[xi] The galleys were a forerunner of today’s prisons; those held in galleys were usually forced to work, in conditions that modern US audiences would recognize as slavery. Most of the manual labor in France in this period was provided by galley prisoners. They were not paid for their work, which was instead considered legal punishment for the “crime” they had committed. Sound familiar?

As oppressive as a term in the galleys might be, it was not the worst of the punishments under the gabelle. Galley imprisonment was the punishment for contraband salt possession; but if someone was found with both contraband salt and a weapon, they were put to death. Similarly, one could be put to death for housing someone who smuggled contraband salt.[xii] So surely with such strict salt laws in place, no one would dare to use “illegal” salt, right? Wouldn’t everyone just buy their salt from licensed merchants to avoid the galleys and the death penalty?

Well, no.

In France, Rome, India, China, the Ottoman Empire and nearly everywhere else salt was highly taxed or produced by government monopoly, we find populations who could neither access nor afford taxed, government-produced salt.[xiii] As a result of this lack of access, time and time again, people inevitably made their own salt. Since no taxes were paid on this salt, in all of these places, all such activity was usually banned as a condition of the salt taxation laws. This was the case in China, India, Rome, France, etc.

Illicit salt production + trade flourished.

But banning an activity by law does not actually stop it from happening. Illicit salt production and trade flourished. In all likelihood this practice probably started almost immediately after the first salt tax was implemented, in ancient China. Illegal salt trafficking then developed throughout China, in India, in Rome, throughout Europe, and presumably much of the rest of the world.

This phenomenon—the production and sale of illicit, untaxed salt by working class communities—points to a dynamic which, as mentioned above, prefigured modern drug laws. And going back to ancient China, salt tax laws have been accompanied by salt-specific police forces. When governments realized how easily salt could be illegally produced and sold, time and time again, they created law enforcement teams specifically to bust this activity. They created salt cops.

Comparable to the modern existence of the Drug Enforcement Agency, narcotics police squads, etc., these agents of the law made careers for themselves by chasing and busting working class people who produced, sold, or used untaxed salt. This happened in ancient China, the Roman Empire, colonial-era Italy, Spain, and France, British-colonized India, and elsewhere.[xiv] The dynamic which resulted from legal and illegal versions of the same commodity enabled the selective criminalization of producers and consumers and created the political template for later drug laws. This is especially evident after the dawn of synthetic drug production, a phenomenon which itself traces back to salt.

A meme made by yours truly.

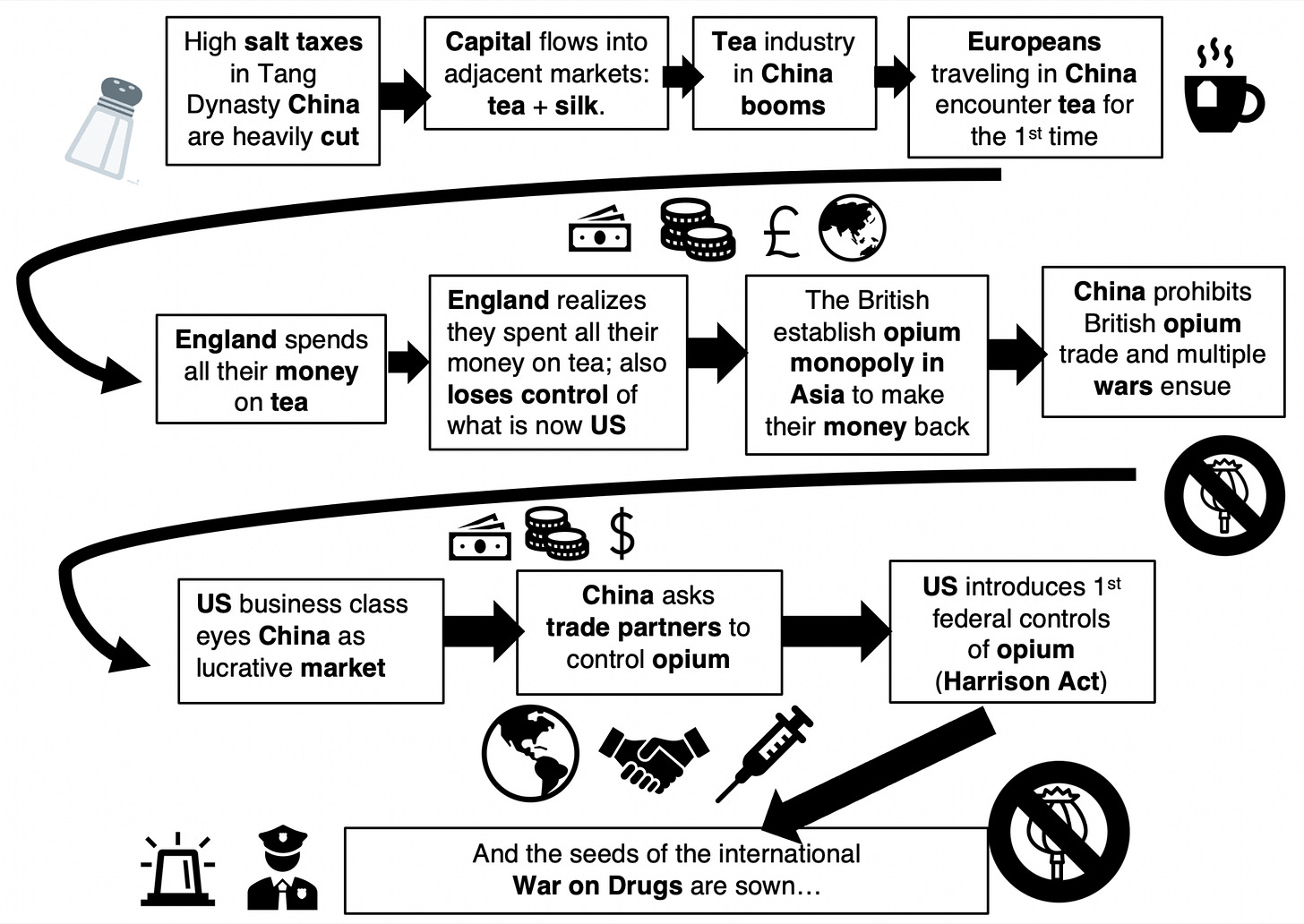

Not only did salt laws provide a legal model for drug laws; arguably, the entire modern drug trade (both legal and illegal) can be traced back directly to the salt taxation system of medieval China. Earlier we learned that after two periods of abolition, the imperial salt tax was reinstated during the Tang Dynasty in eighth century China. This Tang-era salt policy was the beginning of an extended politico-economic process that gradually led to the development of modern drug policy and industry.

II. From the Tang Dynasty Salt Tax to the Marihuana Tax Act

It is in the salt tax of the Tang Dynasty that we see the start of an ongoing political process which has produced in its wake most of the legal and illegal drug trades which exist to this day. In the eighth century CE under the reign of Emperor Daizong, a Salt Commission was established. Additionally, the structure of China’s salt tax system was greatly expanded.[i]

In essence, salt was re-nationalized. Its production was organized under the control of the state, as it had been hundreds of years earlier. The revenue obtained from salt rose dramatically in this period. At one point it made up half of imperial revenue. As a result, the Salt Commission developed “virtually unchecked power,” according to historian Richard von Glahn.[ii] The Chinese state maintained complete control over their salt industry for hundreds of years. It was not until the late fifteenth century that the salt taxation system developed in the eighth century was relaxed.

The loosening of the salt laws in late fifteenth century China catalyzed a growth in trade of tea and silk.[iii] The vast capital which had been accumulated by salt merchants was set loose upon these other commodities, which in turn resulted in their proliferation. This growth in tea trade is particularly worth noting. In the following decades, Europeans traveling through China encountered tea for the first time.[iv] It soon made its way back to Europe.

Reduced salt taxes in late fifteenth century China catalyzed a growth in trade of tea and silk.

Additionally, in the same period (early-mid sixteenth century), laws were introduced in China which required land taxes to be paid in silver.[v] While this may seem irrelevant to the tea boom and the future drug trade, in actuality it was a central factor in the politics which would soon emerge around drug consumption.

With time, tea became immensely popular in England. In the early eighteenth century the British East India Company began to import it in bulk from China.[vi] Chinese merchants, who needed silver to pay land taxes, demanded silver in exchange for the tea.[vii] As tea consumption skyrocketed in England, its trade led to a silver shortage there.

In the midst of this silver shortage, the British lost control of what became the United States in 1776. The simultaneous silver shortage and loss of colonial control pushed the British to expand their colonization of Asia. They violently forced their brand of capitalism upon multiple nations throughout Asia, particularly India, China, and Myanmar (known historically as Burma). A primary goal for the British in Asia was the replenishment of the nation’s silver holdings. Toward that end, they monopolized opium, a common cash crop native to parts of India and China, and sold it to Chinese consumers, accepting only silver as payment.

As tea consumption skyrocketed in England, its trade led to a silver shortage there.

With this, the flow of silver reversed. Gradually, more and more silver left China to pay for opium (and other goods) from western (particularly British) traders. Bullion which had originated in the mines of the western hemisphere and traveled through the hands of European merchants to the pockets of Chinese vendors returned again to Europe.[viii]

However, you may recall that in China, silver was needed for tax payment. The depletion of silver from the Chinese economy negatively affected tax revenue and led to financial difficulty for not only China’s citizens but also its government. As opium was the primary commodity upon which the British relied for silver, the Chinese state focused their attention on the drug. Opium was newly framed as a weapon of imperialism, something which weakened the integrity of Chinese society via its detrimental effect on the nation’s silver holdings and thereby its economy.[ix]

China prohibited opium in the final years of the eighteenth century.[x] Twice in the following century, Britain waged war on China. They did this to protect and expand their business interests there. Because these interests revolved in large part around opium, the wars, known in academic circles as the Anglo-Chinese wars, are known colloquially as the Opium Wars.

Two successive wars and more than a century of foreign aggression permanently ruined any chance of political acceptability for opium in China. As mentioned above, opium consumption was equated with national weakness and banned. When the US eventually followed suit and prohibited opium, the move was motivated primarily by desire to trade with China, who had already banned the drug and expected their trade partners to comply.[xi]

The federal restriction of opium in the US was motivated primarily by desire to trade with China.

Opium use then became highly restricted and socially frowned upon largely because it was an economic inconvenience for China, and for the US corporate and political elite who wanted to expand trade with China. It was from this social landscape that the identity of “the drug user” which has dominated discourse for the last century-plus originated. Opium and its derivatives were increasingly restricted and soon enough other drugs were added to the cue. And thus the stage was set for what became a global paradigm of drug prohibition

To sum up: a loosening of capital enabled by Chinese salt policy catalyzed the growth of the tea trade, which in turn absorbed the silver reserves of Britain, who then, desperate for silver, initiated an opium monopoly in Asia which became a direct cause of the development of modern drug prohibition.

One may wonder whether salt still has anything to do with any of this, and reasonably so. To modern eyes, the connection between salt policy and drug policy may not be especially obvious. However, if one digs deeply into various archives and historical accounts, they will find seemingly countless examples through history in which the two are directly connected.

Salt + opium were mentioned in the same breath in discussions of colonial business.

In the period between the two Anglo-Chinese Wars (or Opium Wars), the areas in which opium was grown for trade with China were overseen by the Board of Customs, Salt, and Opium, itself under the control of the British in Calcutta, India.[xii] The same office which oversaw Britain’s colonial salt monopoly in India also oversaw their opium production.

We find a similar scenario in the French colonization of Southeast Asia. In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, the French colonized what today are Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. In their quest for control, French officials and businessmen sought various ways to generate immense revenue quickly. Salt and other drugs were among their very first considerations for the task.

The revenue generated from the colonial salt, opium, and wine trades funded the development of infrastructure in the region such as railway.[xiii] Sometimes, salt and opium were mentioned in the same breath in discussions of colonial business. Like the British in India, the French in Southeast Asia grouped salt and opium together in policy and business affairs.

The very laws which represent the beginning of drug prohibition in the US themselves resemble salt tax laws.

Keeping with this theme, the very laws which are said to represent the beginning of drug prohibition in the US themselves resemble salt tax laws. Consider as examples the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 and the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937.

The Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 is typically framed as the beginning of opioid and cocaine prohibition in US. But the law did not ban opioids or cocaine outright; instead, it created a system of taxation and licensing. This basic structure—the state as issuer of licenses and collector of revenue—goes back to the salt taxes of ancient China. Further, the bill specifically targeted the salt forms of opium and coca derivatives, such as heroin hydrochloride and cocaine hydrochloride.[xiv] In this sense, the Harrison Act was itself a type of salt tax.

The modern politics of drugs are deeply—if subconsciously—shaped by the premodern politics of salt.

Likewise, cannabis prohibition in the US is often said to have started with the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Again, however, the law did not explicitly ban cannabis. It created a license system overseen by the Treasury Department and imposed admittedly absurd taxes. The law was prohibitive not by definition, but by design. In this way it mimicked the gabelle salt tax of France. Not coincidentally, the bill was backed by the du Pont family, who themselves immigrated to the US from gabelle-era France.[xv]

Considering these facts in sum suggests that the modern politics of drugs are deeply, if subconsciously, shaped by the premodern politics of salt. We have learned how a cascade of historical events which traces back to the salt taxes of Tang-era China laid the groundwork for the development of today’s drug laws. We also saw how the very structure of many of our country’s most formative drug laws themselves resemble various salt tax laws from history. The next topic to which we turn is the intersection between salt, drugs, and warfare.

A cascade of events which traces back to the salt taxes of Tang-era China laid the groundwork for today’s drug laws.

[For more information, check out Salt, Petroleum, War, and Drugs, which further elaborates on the themes introduced above.]

Footnotes

[1] Or, at the very least, things which are caused externally but are reinforced by salt consumption.

[2] Evolutionarily speaking, this is because consuming salt spares us the work of obtaining our sodium and chlorine from other food sources, something which might take hours or days if not for salt. We don’t need actually need salt, but we need sodium and chlorine, and salt is usually the quickest way to get them.

Endnotes

For section I. Salt and the State

[i] On salt tax in twentieth century BCE, see Kurlansky, 29; on salt as “first state monopoly,” see ibid., 12.

[ii] Ibid., 29, 34-35.

[iii] Ibid., 31 and Wu, Luxurious Networks, 35.

[iv] Multhauf, 12, 13.

[v] Ibid., 12.

[vi] Kurlansky, 34-35.

[vii] Multhauf, 11, 12, and 18; information on Arthashastra from Kurlansky, 35.

[viii] Multhauf, 13.

[ix] “A Salt Monopoly.”

[x] Multhauf, 15; see also Kurlansky, 207.

[xi] Multhauf, 14.

[xii] Kurlansky, 231-232.

[xiii] On Ottoman Empire salt monopoly and consequent smuggling, see Fukuyama, The Origins of…, 316.

[xiv] See Multhauf, throughout, and Kurlansky, throughout.

For section II. From the Tang Dynasty Salt Tax to the Marihuana Tax Act:

[i] Roberts, A History of…, 70.

[ii] Von Glahn, The Economic History…, 212.

[iii] Trentmann, Empire of Things, 49.

[iv] Dikötter, Laamann, and Xun, Narcotic Culture, 11.

[v] Roberts, 128.

[vi] Dikötter, Laamann, and Xun, ibid.

[vii] On the role of silver in trade relations between China and Britain, see Wei and Parker, Chinese Account of the Opium War, 1 and 3.

[viii] On the intercontinental flow of silver, see Hucker, China’s Imperial Past, 352 and Graeber, 309.

[ix] Dikötter, Laamann, and Xun, 42-43, and 114.

[x] This was the second time they did so; China had first prohibited opium in 1729. See McCoy, The Politics of…, 5.

[xi] Hart, Drug Use for…, 34; Acker, 33-34.

[xii] Von Bibra, Plant Intoxicants, 97.

[xiii] McCoy, et al, 74; Ladenburg, “The French in…,” 3.

[xiv] The full text of the Harrison Narcotics Act is available at https://www.druglibrary.org/Schaffer/history/e1910/harrisonact.htm.

[xv] Herer, The Emperor Wears…, 55; Colby, Du Pont Dynasty, Ch. 2.

Sources

“A Salt Monopoly.” Mineral Point Tribune, Dec 29, 1887. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86086770/1887-12-29/ed-1/seq-6/

Colby, Gerald. Du Pont Dynasty: Behind the Nylon Curtain. Open Road Integrated Media, Inc., New York, NY. 2014 [originally published in 1974].

Dikötter, Frank, Lars Laamann, and Zhou Xun. Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China. Hurst & Company, London, UK. 2004.

Fukuyama, Francis. The Origins of Political Order. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York, NY. 2011.

Graeber, David. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Melville House Publishing, Brooklyn, NY. 2014.

Hart, Carl. Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear. Penguin Press, New York, NY. 2021.

Herer, Jack. The Emperor Wears No Clothes. AH HA Publishing, Austin, TX. 2010 [originally published in 1985].

Hucker, Charles O. China’s Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. 1975.

Kurlansky, Mark. Salt: A World History. Penguin Books, 2002. New York, NY.

Ladenburg, Tom. “The French in Indochina,” from “Critical Issues and Simulations Units in American History.” Digital History. University of Houston, 2007.

McCoy, Alfred. The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade. Lawrence Hill Books, Chicago, IL. 2003.

Multhauf, Robert P., Neptune’s Gift: A History of Common Salt. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. 1995 [originally published in 1978].

Roberts, J. A. G. A History of China. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY. 2006.

Trentmann, Frank. Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, from the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First. HarperCollins Publishers. New York, NY. 2016.

Von Bibra, Baron Ernst. Plant Intoxicants: A Classic Text on the Use of Mind-Altering Plants. Healing Arts Press, Rochester, VT. 1995 [originally published in 1855].

Von Glahn, Richard. The Economic History of China: From Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, 2016. Cambridge, UK.

Wei Yüan and E. H. Parker, Chinese Account of the Opium War. Kelly & Walsh, Limited, 1888. Shanghai, China.

Wu, Yulian. Luxurious Networks: Salt Merchants, Status, and Statecraft in Eighteenth-Century China. Stanford University Press. Stanford, CA. 2017.

Photo credits

Sea salt from Gryffon Ridge Spice Merchants: https://gryffonridge.com/product/maldon-sea-salt-flakes/

Pile of unidentified powdered drug from Advanced Science News: https://www.advancedsciencenews.com/identifying-illicit-drugs-in-powdered-mixtures-using-magnetic-levitation/

Salt shaker from Chemical & Engineering News: https://cen.acs.org/biological-chemistry/biochemistry/Salt-revs-allergy-activating-immune/97/web/2019/02

Cocaine from Recovery First Treatment Center: https://recoveryfirst.org/cocaine/methods-of-use/

Crack and meth from Drug Free Kids Canada: https://drugfreekidscanada.org/prevention/drug-spotlights/illegal-drugs/

MDMA from Alcohol and Drug Foundation: https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/mdma/

Epsom salt crystals from Science Notes: https://sciencenotes.org/how-to-grow-epsom-salt-crystals/

Click here to order your copy of Drugism.

#drugism #drugs #history #gabelle #salt #tax #tea #opium #heroin #fentanyl #cannabis #cocaine #crack #MDMA #legalize #regulate #savelives