Mary Jane Superweed + the Commodification of DMT

This mysterious pamphlet from 1969 was a harbinger of things to come

The following is an excerpt from p. 144-145 of Chapter 3, “Everywhere, All the Time: DMT and Drugism” from my book, Drugism (2022):

[Note: today’s excerpt picks up where “DMT Hits the Airwaves” left off.]

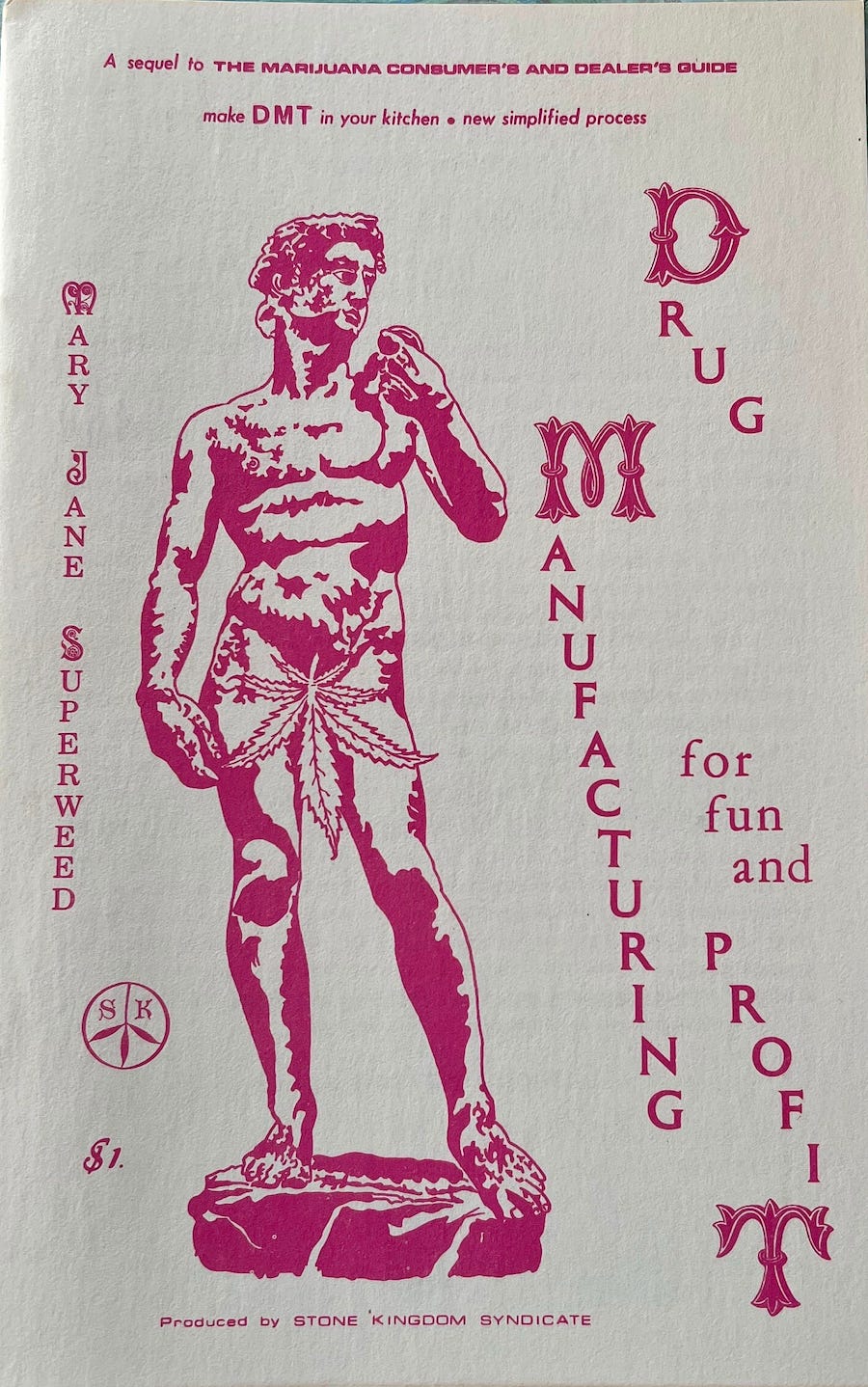

A recipe for DMT appeared in 1969 as part of a pamphlet titled Drug Manufacturing for Fun and Profit. On its cover, the d in “drug,” m in “manufacturing,” and t in “profit” are drastically larger than the rest of the print, capitalized, and bold. The result: the letters “DMT” are seen floating across the cover. At the end of the recipe, the author, under the pseudonym Mary Jane Superweed, cautioned “DMT is a powerful psychedelic. Wisdom should govern the frequency of its use.”[i]

This little bit of guidance is meaningful. It clearly indicates that DMT is not something to be taken lightly, so to speak. It also reveals an ongoing association between DMT and power, whereby powerfulness becomes one of the traits most closely associated with the drug. This theme would be embraced by the McKennas and others in the decades to come, whether consciously or not. In Mary Jane Superweed’s pamphlet we also see a clear juxtaposition of the notions of DMT production and profit. In essence, it introduces a capitalist concept—profit—to a drug which originates in precolonial indigenous cultures.

What are we to make of this? To some, it comes as no surprise—drugs are things to be sold and consumed. In a capitalist framework, they naturally lend themselves to profitmaking. But many drug enthusiasts are not so likely to associate DMT with profitmaking. DMT is however often seen as something valuable, possessing a mystical aura which beckons the user to pursue it. Herein we see that for every stoner tripped out on DMT, there is a flip side—an enterprising chemist or trafficker looking to earn money.

Everyone who pays money or favors to obtain “powerful” substances engages in this dance of power, whether or not they realize it. The “mystical,” supposedly transcendental experiences which are so often ascribed to DMT come from somewhere physical, concrete—they come from people producing and selling drugs. If one is lucky, they are gifted rather than sold.

The lesson here is that no drug can escape the clutches of capitalism, unfortunately. The moment something is conceived as a drug, it becomes something to be consumed by others, at a price. “Drug culture” is, in large part, the amalgamation of social practices around the acquisition and consumption of commodified substances. We must not lose sight of this in our evaluation of “DMT culture”—whatever such a thing may prove to be. In social practices around DMT, notions like power and profit are arguably just as central as notions of consciousness expansion, mysticism, etc.

Mary Jane Superweed wrote about synthesizing DMT for profit in 1969. The following year, DMT and several of its analogues were included in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act.[ii] Henceforth, using, possessing, or manufacturing DMT became illegal except for those with federal approval.

By the early 1970s, the fact that DMT could be found in Mimosa hostilis bark was publicly available in the US.[iii] But much, probably most, of the DMT available in the US was synthetic through the rest of the twentieth century. This would not change until the early 2000s. The resurgence of DMT in the 2000s was deeply inspired by the work of Rick Strassman in the 1990s, who became one of the first scientists to conduct public, legally sanctioned research on tryptamines since the field was largely shut down in the early ‘70s. It is to this story that we now turn.

[Continue reading here.]

Hey, interesting piece! I recently subscribed for the year-long sub - can you contact me to discuss getting a copy of the book as advertised in the subscription?

John Mann, member of The Church of the Tree of Life. A good friend of mine was involved with these pamphlets in the 1970’s in California.