King Sugar + the Big Five

The sugar industry backed the colonization and annexation of Hawaii, paving the way for statehood

The following is an excerpt from p. 96-99 of Chapter 2, “Sugar is the Knife: The World’s Favorite Drug” from my book, Drugism (2022):

[Note: this excerpt picks up where “Sugar and Colonization” left off.]

Unfortunately, colonial extraction of sugar and labor never really stopped. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, another imperial power came to dominate the global sugar market: the United States.

Sugar has been important for US economic policy from the beginning.[i] Most of the US is too far north to be suitable for cane sugar cultivation. As a result, people in the US have relied on numerous lands scattered across the globe for their sugar supply. The desire for sugar was the driving factor behind the annexation of Hawaii. And something similar would likely have happened to Cuba, were it not for the Cuban Revolution.

Demand for sugar in the US grew steadily from the period of independence onward. The Civil War revealed the instability of US sugar supply chains, however. By the end of the nineteenth century, sugar was at “the top of the US political agenda.”[ii] In 1887, seventeen sugar refineries in the US were amalgamated into a trust, the American Sugar Refining Company. The trust, it is estimated, “controlled 98 per cent of the industry.”[iii] They are still around today, rebranded as ASR Group (as in American Sugar Refining). They own Domino Sugar, among many other brands.[iv]

While notable sugar businesses emerged in Louisiana and Texas, these could not supply enough of the stuff to the rapidly growing US population. Most of the sugar consumed in the US instead came from places like Hawaii, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.[v]

The history of Hawaii is rich and fascinating in its own right. There are many great writings about precolonial Hawaii, and the politics of its subsequent occupation which interested readers can refer to. The story of its initial contact with people of European descent is complex and beyond the scope of this chapter. However, let it suffice to say that, like the Caribbean, Hawaii’s colonization was a long and violent process. And many decades before its annexation into the US, we find US sugar interests in Hawaii’s history. They would come to dominate its economy and its politics.

In his study of the South Pacific islands, J. C. Furnas wrote that sugar was first introduced to Hawaii by migrants from other Pacific islands long before European colonization. Francine du Plessix Gray, in Hawaii: The Sugar-Coated Fortress, wrote “cane has always grown wild in Hawaii.”[vi] If sugar cane did indeed originate in New Guinea, it is not inconceivable that some related species might be native to Hawaii, as du Plessix Gray seems to suggest. Whether or not sugar is truly native to Hawaii, indigenous Hawaiians had already developed uses for it before colonists started to commercialize it there.

The first large commercial sugar plantations in Hawaii were started in the 1830s by missionaries from Boston (a typical pattern in colonization: “give us your land now and you’ll get into heaven later”). When the Civil War cut off Union access to Confederate sugar from the Louisiana and Texas plantations, US business interests responded by importing more sugar from places like Hawaii.[vii]

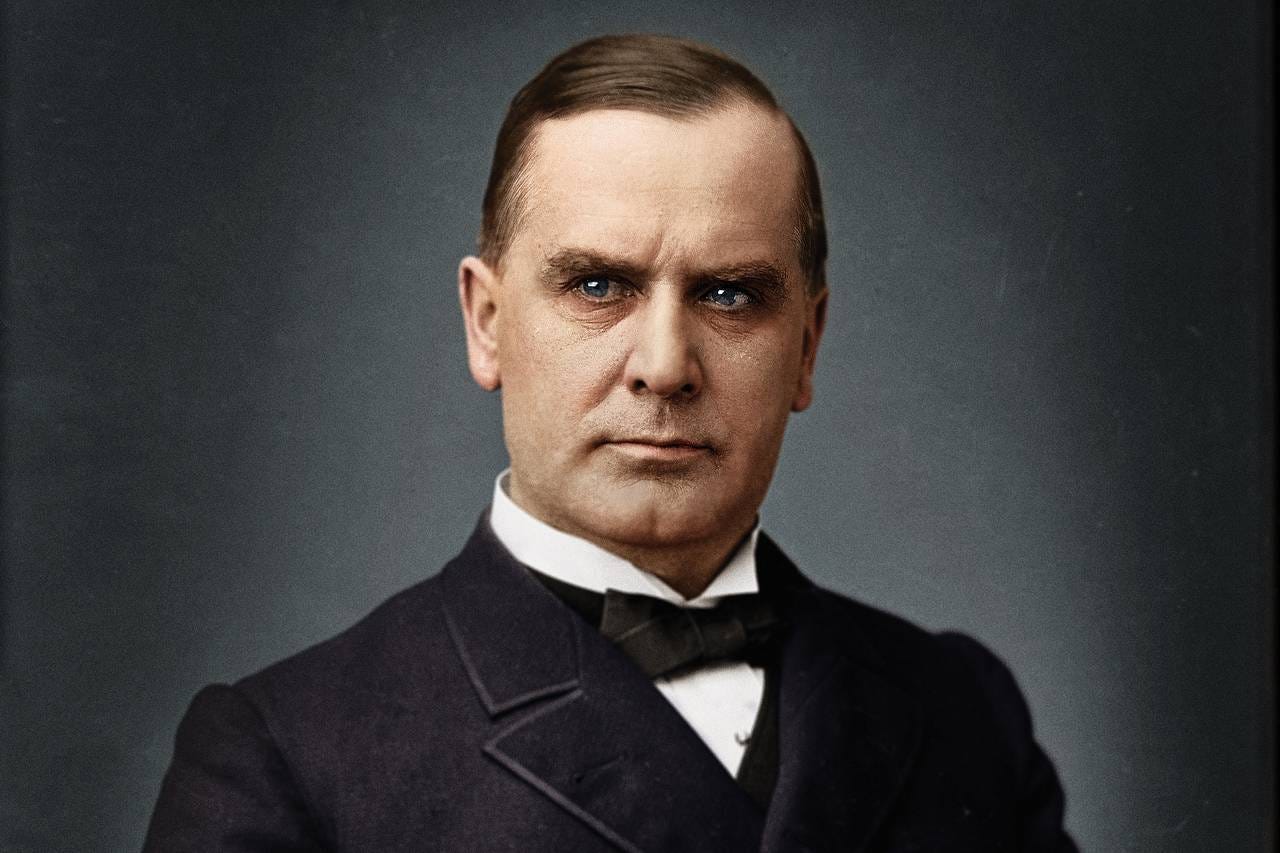

Still not yet a state or territory, Hawaii got an upper hand on the US sugar market after the Civil War, which it held until 1891. That year, the McKinley Act passed, which “removed duties on all imported sugar but also granted a bounty on sugar home-grown in the United States.”[viii]It was introduced by Senator William McKinley, who shortly thereafter was elected President. The McKinley Act greatly upset the Hawaiian sugar capitalists, who now had to compete with Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the US’s own domestic farmers for the sugar market.

It was in response to this loss of power that the sugar tycoons who ruled Hawaii’s economy orchestrated Hawaii’s annexation in 1898. The Hawaiian corporate elite then convinced the native Hawaiian Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole to become a Republican and run as a congressional representative for Hawaii. He did, and he won.[ix]

By this period, the 1890s, four fifths of the arable land in Hawaii was controlled by a small handful of sugar interests. From the period immediately before annexation through the Great Depression, Hawaii’s sugar production increased fourfold. Almost all of it went to the US. Even before Hawaii’s annexation, the US had obtained control of Pearl Harbor by agreeing to remove duties on Hawaiian sugar.[x]

In Hawaii, the stuff is given a royal pronoun: King Sugar. For many years, the Hawaiian sugar industry was controlled by “the Big Five,” a group of five enormously wealthy sugar interests in Hawaii.[xi] At the height of their power, 96% of the sugar produced in Hawaii came from the Big Five’s plantations. They were Hawaii’s sugar cartel.

The rapid increase in sugar production seen in Hawaii was not possible without a rapid increase in labor force. And, like anywhere else cane was grown, Hawaii’s sugar planters faced many issues in their attempt to obtain sufficient labor. A primary problem was that every generation who worked on the cane fields generally expected their children not to work on cane, but to find other jobs. The labor was rough on the body and the mind, and plantation workers had little or no opportunity for economic advancement.

As Hawaii’s plantation economy continued over successive generations, new populations of laborers were brought in to meet the labor demands of the industry. It had started with Native Hawaiians, forcefully subjugated to labor by European and American colonizers. Then came Chinese, and then Portuguese, then Korean, Japanese, Filipino, Puerto Rican, Spanish, German and Russian workers, all of whom cycled through the sugar cane plantations of Hawaii in massive numbers.[xii]

“Between 1850 and 1930,” according to du Plessix Gray,

some four hundred thousand men, women and children were transported to the Hawaiian Islands as a result of the sugar planters’ relentless search for cheap and docile laborers.[xiii]

When they got paid at all, the various populations of laborers were paid different wages according to their ethnicity. People of European descent were always paid the most. People of Hawaiian or Asian ancestry were paid a small fraction of what Euro-Americans made.[xiv]

Du Plessix Gray writes of Hawaii in this period as a site of enormous “psychological violence,” as well as physical violence. Even after sugar plantation workers gradually won the right to compensation, their wages were often withheld. It was not until the 1940s that union activity in Hawaii was able to muster serious support.[xv] But there had been pro-labor sentiment there for decades.[xvi] And since most of Hawaii’s economy was ruled by a single commodity, most of Hawaii’s labor activity, in turn, revolved around it: sugar.

Throughout the early twentieth century, tens of thousands of acres of land which had been legally reserved for people of Hawaiian ancestry were instead sold to the US military and sugar companies. The institution through which this was orchestrated, the Hawaiian Homes Commission was, for years, headquartered on the island of O’ahu, at the bottom of Mount Tantalus.[xvii]

The top of Mount Tantalus, according to du Plessix Gray writing in 1972, was “the hippies’ favorite site for tripping.”[xviii] I wonder what the people tripping on Mount Tantalus in the seventies thought of sugar, and the brutalities which Hawaiians underwent to produce such a sugar boom. I suspect some of them may have been sipping on sodas or eating candy themselves.

And whether or not du Plessix Gray’s trippers were aware of the gravity of sugar, it would not be the first time we find psychedelic culture and the sugar industry juxtaposed. This also occurred in Cuba, in a way that has since impacted the lives of millions of people around the world.