DMT Bureaucracy in the '80s + '90s

Carl Peck, Daniel X. Freedman, + the politics of DMT research

The following is an excerpt from p. 148-149 of Chapter 3, “Everywhere, All the Time: DMT and Drugism” from my book, Drugism (2022):

[Note: See “At Stanford in the ‘70s…”]

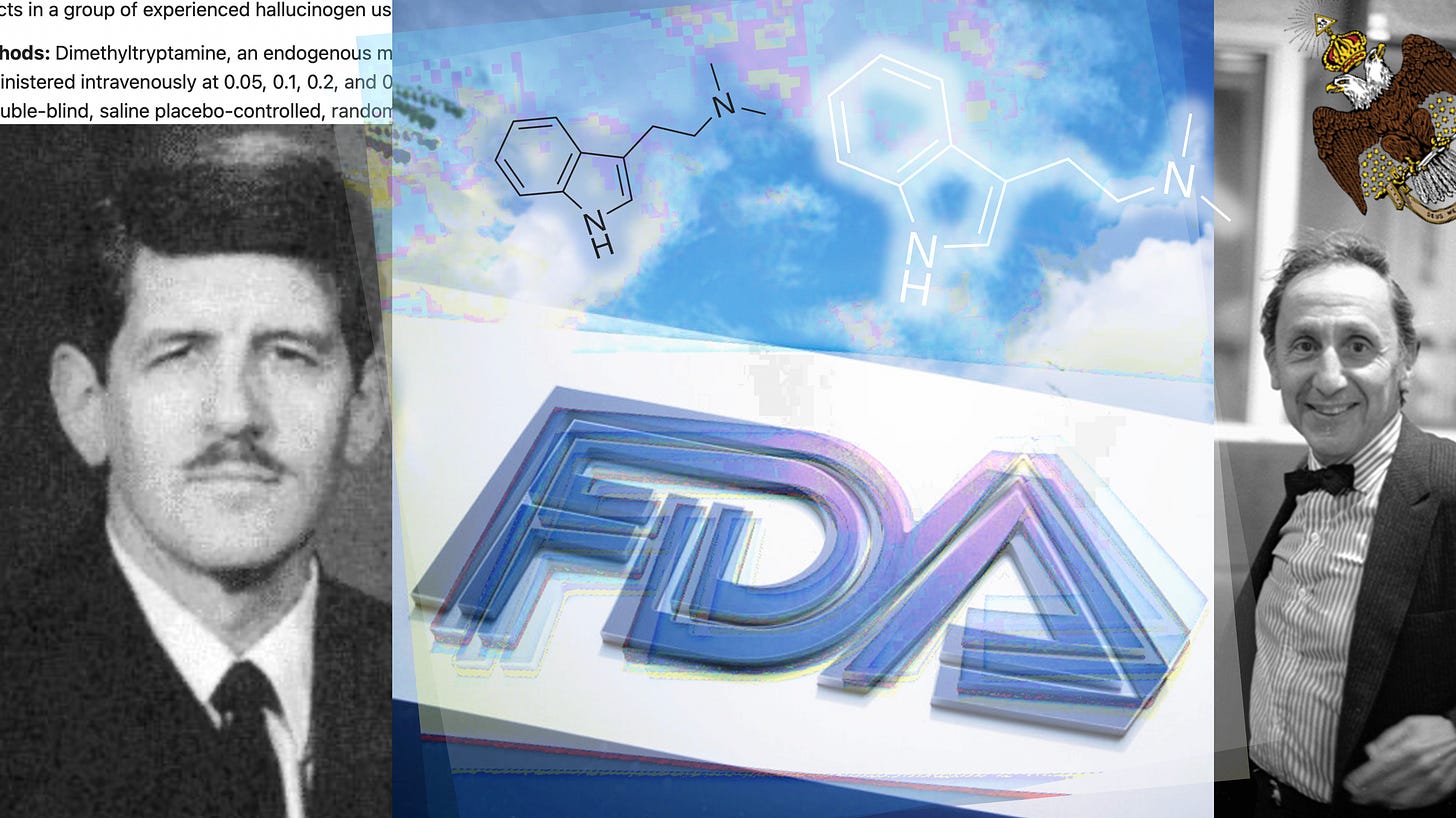

In 1987, an important change occurred at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA): someone named Carl Peck was made the head of the FDA’s center for drug evaluation.[i] Peck had extensive connections to the Department of Defense, and his appointment to the FDA marked a turning point in the politics of drug research. Most notably, under Peck’s guidance, the FDA started approving psychedelic research projects. In 1990, Rick Strassman received permission to study DMT.[ii]

In the interim between Strassman’s DMT application and its approval, he managed to secure funding from the Freemasons. This was in large part thanks to his friendship with Daniel X. Freedman, mentioned in the previous excerpt.

Discussing Freedman’s impact on his research, Strassman wrote that Freedman “advocated for these projects at all levels and was instrumental in my obtaining crucial early funding.”[iii] Some of this funding came from a prominent branch of the Freemasons known as the Scottish Rite Foundation—thanks to Freedman. Freedman sat on the Foundation’s scientific review committee. When Strassman learned that the group had a history of funding DMT research, he applied for a grant. With Freedman’s help, he got it, in late 1989.[iv]

Freedman shaped the study in other ways, not all of which were beneficial. According to Strassman, Freedman’s influence “set the stage for certain problems that developed later on in our research.” Freedman believed that studying the mental effects of DMT, or its applications to psychotherapy, would “result in irrational enthusiasm, questionable results, and scientific controversy.”[v] Instead, he insisted that the research focus solely on biometric data, dosage, and safety. Strassman disagreed with Freedman on this point but, out of respect, took Freedman’s advice and designed the study to focus on objective data rather than subjective experience.

In 1988 Strassman had applied to do the study; he had secured funding by 1989, and the study was approved in 1990. However, before he could start giving DMT to volunteers, there were a number of bureaucratic hurdles he still had to jump. Among the most important of these was the matter of finding DMT suitable for administration.

Initially, Strassman obtained a small amount of laboratory grade DMT to use as a standard against which to measure DMT in body fluids. This DMT came from Sigma-Aldrich, a multinational chemical manufacturer owned by Merck.[vi] Finding the drug was not difficult; as Strassman recalls, the DMT was listed in Sigma-Aldrich’s catalogue.

However, for bureaucratic reasons, Strassman was not allowed to use Sigma-Aldrich’s DMT for the volunteers’ doses. Theirs was laboratory grade, not clinical grade, so it was off limits for human administration. For clinical grade DMT, Strassman went to David Nichols, who, at the time, was at Purdue University.[1] Nichols had also produced the MDMA for MAPS’ early studies.[2] Nichols also provided input on the dosages to be used for the research, as did Stephen Szára.[vii]

As Strassman notes regarding the preparation of DMT, “The salt form was necessary so the DMT would dissolve in water.”[viii] This may seem trivial to most readers, but it points to the legacy of salt within the field of drug research and development. As we learned in Chapter 1, drugs are often prepared in their salt forms because of the long shelf-lives and ample bioavailability that result. Additionally, the placebo used in Strassman’s research was salt water.[ix]

Strassman has always stated that without Daniel Freedman’s ‘orchestration & influence’ Ricks DMT research would not have launched with successful results. Danny was given the parameters and he relayed them to Rick. Silver lining-the study was well documented.