DMT as Commodity

Consumerism meets the "spirit molecule"

See photo credits below.

The following is an excerpt from p. 164-165 of Chapter 3, “Everywhere, All the Time: DMT and Drugism” from my new book, Drugism (2022):

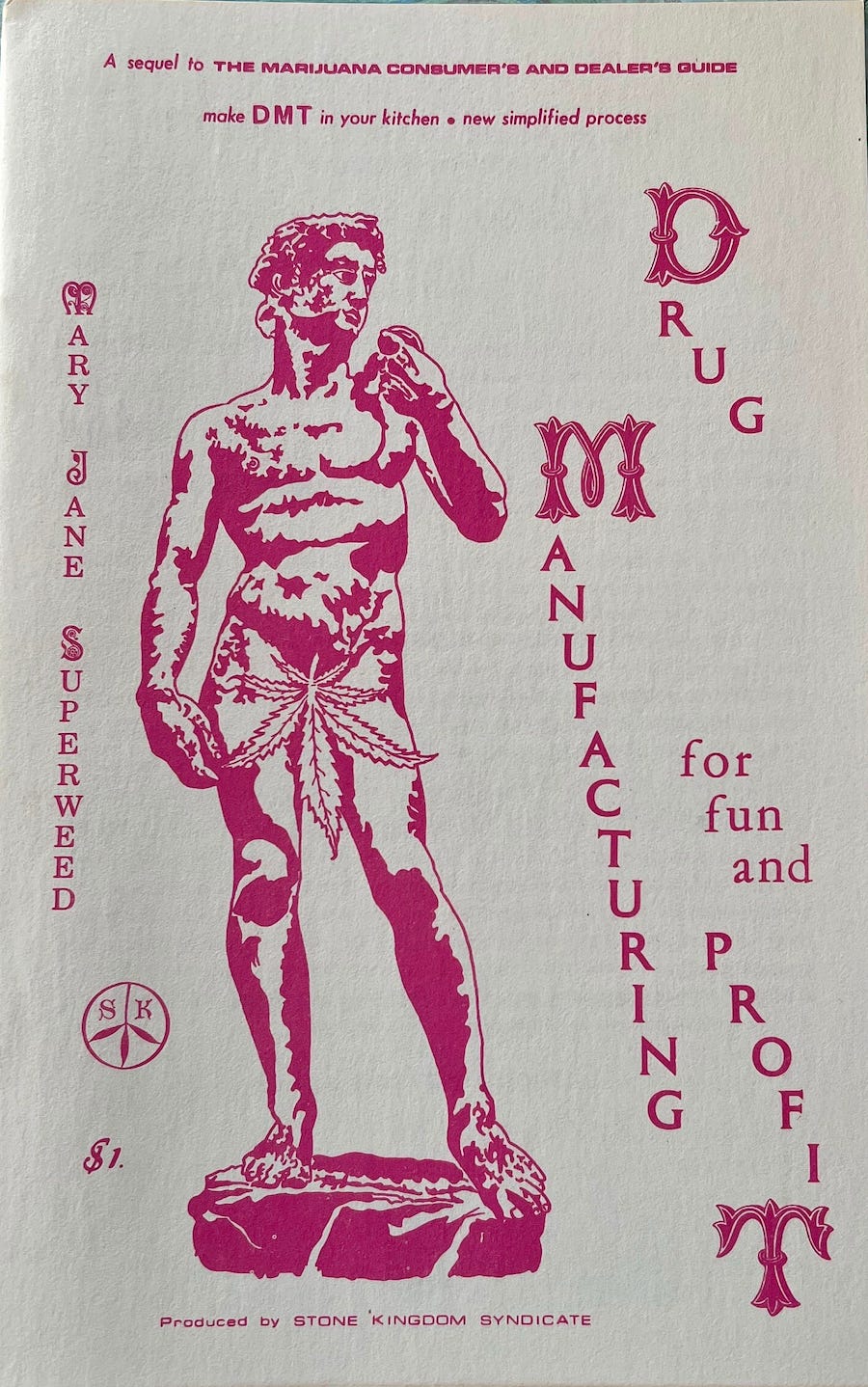

DMT is a commodity. Arguably it had already attained such status in 1969 when Mary Jane Superweed published Drug Manufacturing for Fun and Profit. Certainly, DMT has been commodified in recent years. The combined impact of clinical research on DMT, its increased distribution, and its use (in the form of ayahuasca) in institutional religions such as UDV—all, to some extent, state-sanctioned—has led to a surge in interest in the drug. It has also resulted in a not insignificant number of dollars spent on the stuff, in one way or another. As such, we are apt to recognize that DMT has become a permanent, if modest, fixture in the drug economy.

And, like any other commodity, a cult of consumerism has formed around DMT. It is fetishized. It is the subject of obsession, craving, and fantasy. And while some of its headier enthusiasts may insist that DMT always be gifted and never sold, plenty of people sell it. Despite its illegality for anyone without a Schedule I license, DMT has become a trendy and in-demand drug among enthusiasts in the US and across the world.

Like any other commodity, a cult of consumerism has formed around DMT. It is fetishized. It is the subject of obsession, craving, and fantasy.

Terence McKenna’s fascination with DMT has since been replicated in an untold number of people, who litter the internet with trip reports, extraction recipes, and blogposts praising “the spirit molecule.” A small but rapidly growing body of literature and scholarship on the drug is developing, much of it replete with references to at least one of the McKenna brothers’ work. The bodies of knowledge built and disseminated about DMT revolve heavily around concepts introduced by the McKenna brothers and Strassman.

The result is that DMT is typically associated with intense, out-of-body experiences, entity contact, and mystical transcendence. This is what many drug users are told to expect when they first encounter the substance, if anything. As we saw [earlier in the book], McKenna’s work spawned wider interest in DMT in the ‘90s. In the midst of this tidal influence, we find one D. M. Turner (a DMT-inspired pseudonym), a rather experienced drug enthusiast who published some seminal work on the subject in the ‘90s.

The same year that Douglas Rushkoff published Cyberia, 1994, Turner published The Essential Psychedelic Guide. The book is a stellar collection of detailed history, dosage information, and trip reports on a wide variety of drugs. In it, Turner (like Rushkoff) acknowledged the influence of Terence McKenna in DMT’s growing reputation.[i] He referred to the drug as “candy for the mind.”[ii] Interestingly, Turner also made a comment on DMT which was quite similar to one made decades earlier by Al Hubbard when he wrote, “trying to resist DMT’s overwhelming influence and the inevitable dissolution of the identity will be unpleasant, and it won’t work.”[iii] In many ways, his writing on DMT exemplifies attitudes toward the drug among its enthusiasts.

Turner described DMT as “candy for the mind.”

The demand for DMT had grown enough by the late ‘90s that multinational drug traffickers started to harvest Acacia trees in Australia as a source of DMT to be sold primarily in Europe.[iv] And by then, ayahuasca had become a noted magnet of drug tourism in the western hemisphere.[v] As noted earlier [in the book], this phenomenon owes in part to the activities of William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and others in the 1950s. The practice of traveling to Central and South America to use ayahuasca in its place of origin has since become increasingly popular among drug enthusiasts.[vi] It is framed variously as spiritual experience, healing, etc. and has become a veritable industry, if a small and dispersed one at that.[vii]

Unfortunately, the ayahuasca circuit that has emerged in recent years has also catalyzed things far less benign than healing, indeed rather malevolent things such as theft, psychological manipulation, sexual abuse, and even murder. While they are not necessarily common, neither are they unheard of. As nefarious actors have embedded themselves in ayahuasca tourism (as they doubtlessly will in any field), the urgency of fostering a mature and respectful attitude toward DMT and related substances has only increased.

In the interest of harm reduction, it seems necessary to also discuss the mental trauma, confusion, and potential habituation that can ensue from use of the drug. In my own experience, such factors were equally if not more so present than the desirable ones, though I did not quite realize it at the time.

The urgency of fostering a mature and respectful attitude toward DMT and related substances has only increased in recent years.

[Continue reading here.]

Endnotes

[i] Turner, The Essential Psychedelic…, 50.

[ii] Ibid., 47.

[iii] Ibid., 23.

[iv] St John, 163.

[v] Dobkin DeRios, “Drug Tourism in…”

[vi] St John, 178.

[vii] But there is a deceptively fine line between respecting indigenous cultures and practicing manipulative colonialism.

Ramon Pane, the first non-indigenous person to witness and note the use of yopo (that we know of), accompanied Columbus on his violent, destructive colonial ventures through the Caribbean. The drive to explore, dominate, and extract resources was also at play in the subsequent work of Alexander von Humboldt and Richard Spruce.

Still today, the legacy of colonization is practically inseparable from the microcultures that have formed around DMT and ayahuasca. Graham St John describes modern DMT use in terms that are utterly colonial: “undertaking private vision quests as solo explorers or in small groups, experimentalists will seek to maximize the potential for ontological and metaphysical challenge by smoking DMT in geophysical regions remote from home”; see St John, 333.

Sources

Dobkin DeRios, “Drug Tourism in the Amazon.” Anthropology of Consciousness 5(1):16-19. Mar 1994. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1525/ac.1994.5.1.16

St John, Graham. Mystery School in Hyperspace: A Cultural History of DMT. Evolver Editions, Berkeley, CA. 2015.

Turner, D. M. The Essential Psychedelic Guide. Panther Press, San Francisco, CA. 1994.

Photo credits

Photo of cover of Drug Manufacturing for Fun and Profit from https://www.etsy.com/in-en/listing/1179155549/drug-manufacturing-for-fun-and-profit

Photo of William S. Burroughs from https://wilderutopia.com/traditions/ayahuasca-fake-shamans-and-the-divine-vine-of-immortality/

Photo of DMT crystals from https://stickyricesyd.tumblr.com/post/59060060808/dreamsdieintheshadows-dmt-crystals/amp

Photo of cash from Wikimedia Commons at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Money_Cash.jpg

#drugism #drugs #drug #DMT #commodity #commodification #consumerism #capitalism